My novel writing process is a combination of unplanned inspiration and detailed planning. Life, observation and eavesdropping inspire the core idea. It bakes in my subconscious and gradually rises to the forefront of my mind. Once the premise of the book fully reveals itself to me, I frantically jot down as many notes as possible.

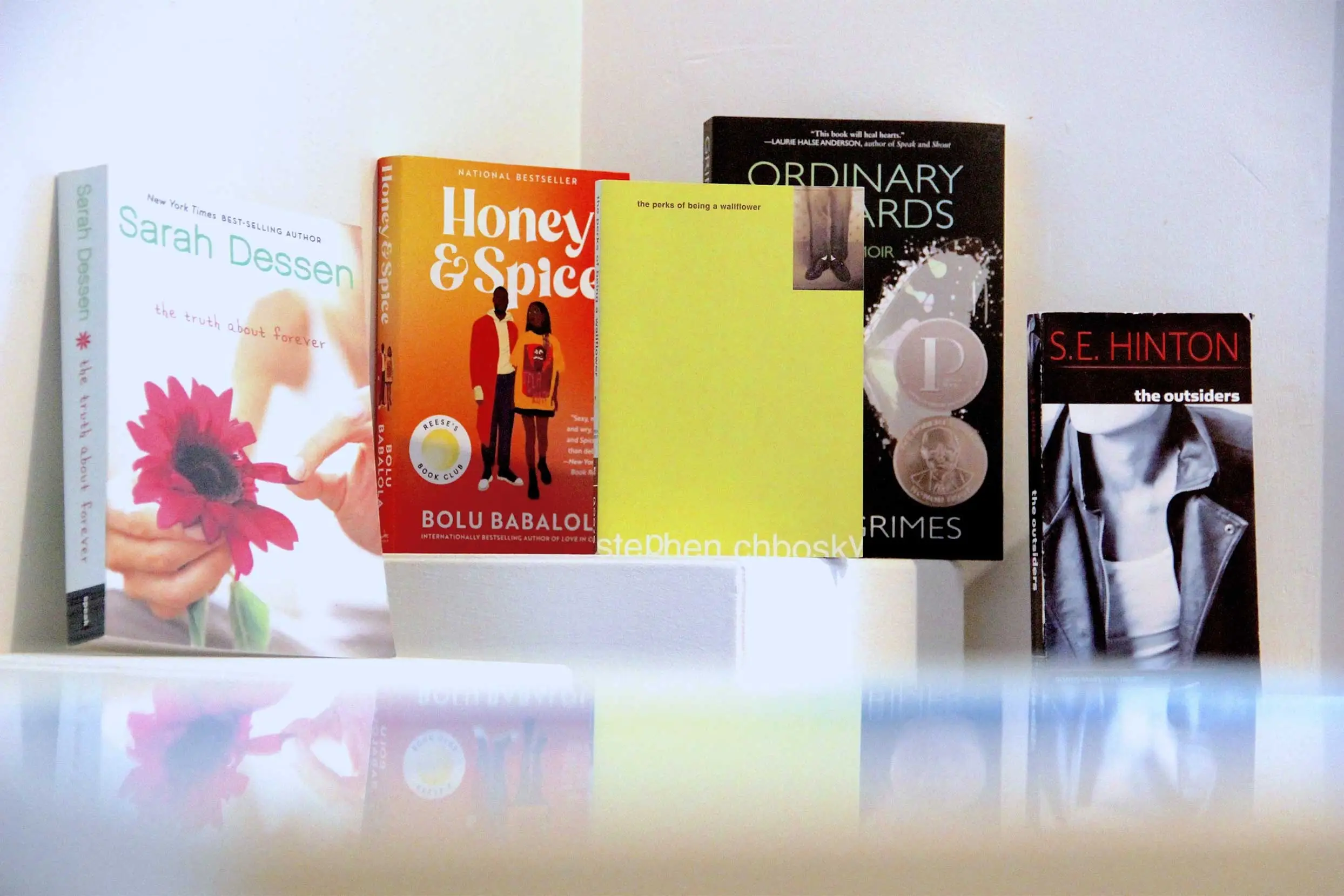

This ideation journey is different from authors who set aside time to actively brainstorm, often with a goal, audience or genre in mind. For me, the idea comes naturally, a privilege I am grateful for. I don’t think about genre or audience until after the book is written, thoroughly edited and ready to be published.

After reviewing my notes on the premise of the book, I create the following planning documents:

Overall Book Notes

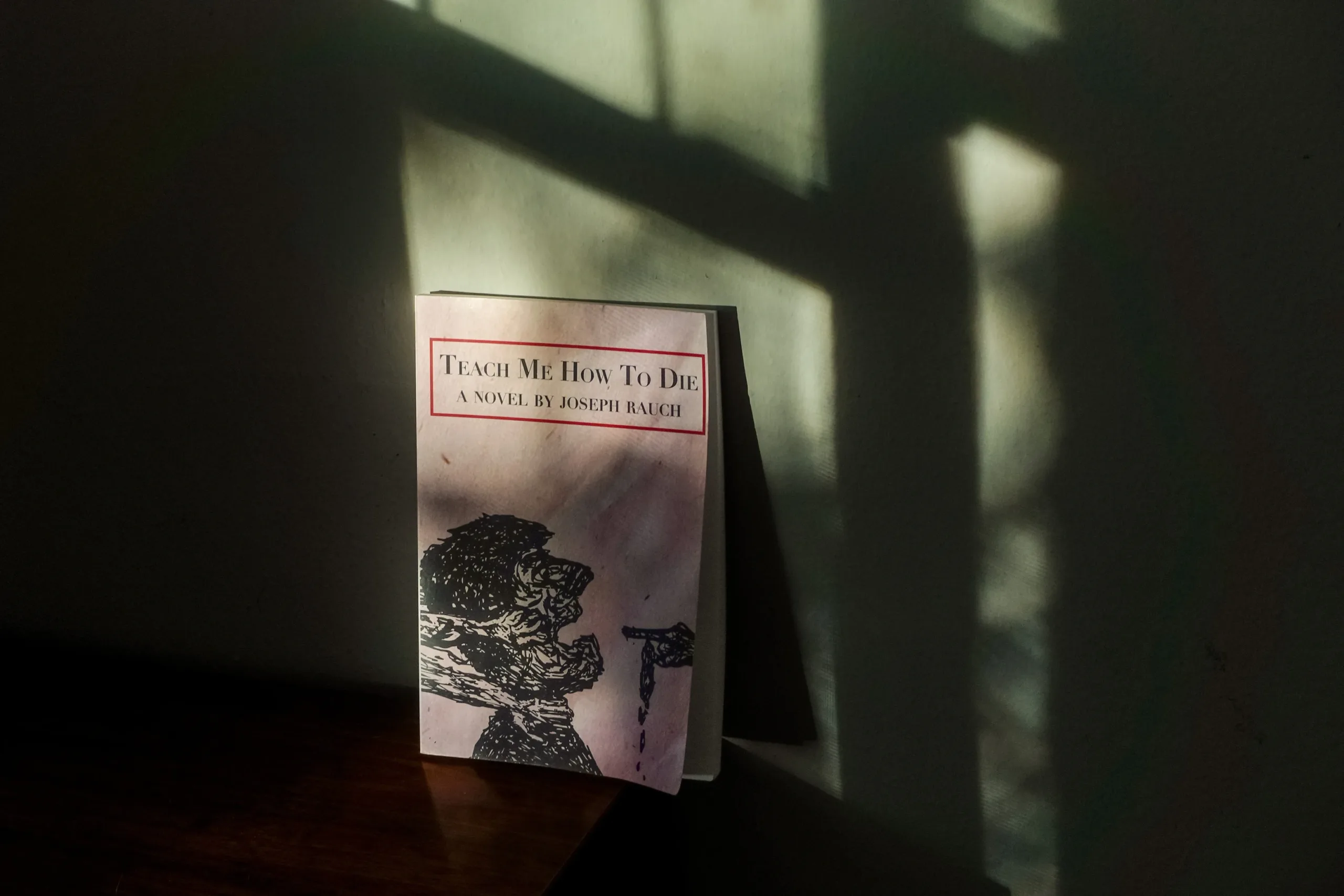

This is where I write down the basic premise of the book. For “Teach Me How To Die,” it was something like: “depressed, nearly suicidal widower dies, experiences his repressed urges to sin, then travels through my imagining of the afterlife with a bitter guide based on Virgil from ‘The Inferno.’”

Sometimes this document is short. Other times I add notes to it, especially if I think big aspects of the planning could change before I start writing the novel.

Prose and Dialogue Notes

When a line of prose or dialogue pops into my head and makes me excited, I write it in this document or jot it down in a physical notebook. To ensure I remember how to use the line if it ends up fitting well in my draft, I also write notes explaining the context of the line.

Character Profiles

My characters are fusions of:

- Pieces of my self-perception

- Pieces of people I know in real life

- Pieces of famous people/historical figures I study and imagine but haven’t met

- Pieces of other fictional characters I find interesting or have related to

- Pieces of how other people perceive me

- Pieces of the person I might have become had I made different choices or had a different background

- Opposites of the above

Chester, the main character of my second novel, “The Last of the Mentally Ill,” is the opposite of me in terms of his social behavior. I’ve rarely had social anxiety. I talk a lot, sometimes too much.

Internally, Chester and I are similar. Many of the thoughts he expresses are slightly altered versions of mine.

To flesh out my character profiles, I also leverage my journalistic background. I conduct thorough research and interview people.

This step is especially important for characters whose identities are different from mine. While writing “Teach Me How To Die,” I didn’t interview people much because the main character is also a biracial atheist. With “The Last of the Mentally Ill,” which features several Black main and supporting characters for reasons I explain in the afterword, research and interviewing was a crucial and extensive part of my due diligence.

Whether I write the character profiles in one document or create a separate document for each profile, I always organize my notes in these sections:

- Personality traits

- Motivation, goals and desires

- Backstory

- Insecurities and anxieties

- Worldview

- Arc: how the character changes internally and externally, or a justification for why they don’t change

- Physical appearance

- Voice sound

- Manner of dialogue

- Relationships with other characters

Plot Outline

Because the Overall Notes document covers the plot at a high level, this document is a list of every scene and event in the story. I spend a lot of time thinking about the order of scenes. If perspective changes from one scene to another, I leave a note to ensure I remember once I begin writing.

Having a list of scenes helps me set goals and pace for my writing. When feasible, I try to complete the first draft of a scene during every one of my novel writing sessions.

Rhetoric Goals

What lessons or statements do I want readers to take away? How can I convey rhetoric in a way that isn’t sanctimonious or overly direct? This document is where I try to answer these questions.

Setting Notes

This document is relevant when I include real world settings in my novels. For “The Last of the Mentally Ill,” I walked around the parts of Manhattan I wanted to include in the book. I wrote detailed notes and musings on everything I saw.

What would my characters think and say about this setting? How would they react to it? Would they like it? If multiple characters are in a setting, would the setting become a topic of conversation between the characters?

The Actual Writing

Once the above documents are done, I print them out and keep them handy every time I write. I try to go scene by scene from beginning to end. Sometimes I make small changes to the documents.

I’ve met a few authors who don’t do any planning, or at least not this much. They simply write and see where the story takes them. I can imagine this approach has upsides mine does not.

I have noticed, however, that readers have complained more about the endings of novels by authors who write this way. It makes sense that an unplanned writing style would increase the risk of plot holes. My approach may be less spontaneous, but I have yet to see a reader critique my endings.

Once the writing is done, I move on to editing. I have a process for that, too.