I care deeply about ensuring my novels have the highest quality writing I’m capable of. With “The Last of the Mentally Ill,” I have developed an editing process I plan to repeat for my in-progress and future novels.

It starts with me. I do two initial edits, one for readability and another for everything else.

The Word doc file name for my first draft is “novel title draft 1.” Before I begin editing, I duplicate the document and relabel the file “novel title draft 2.” With every round of editing, I repeat this process.

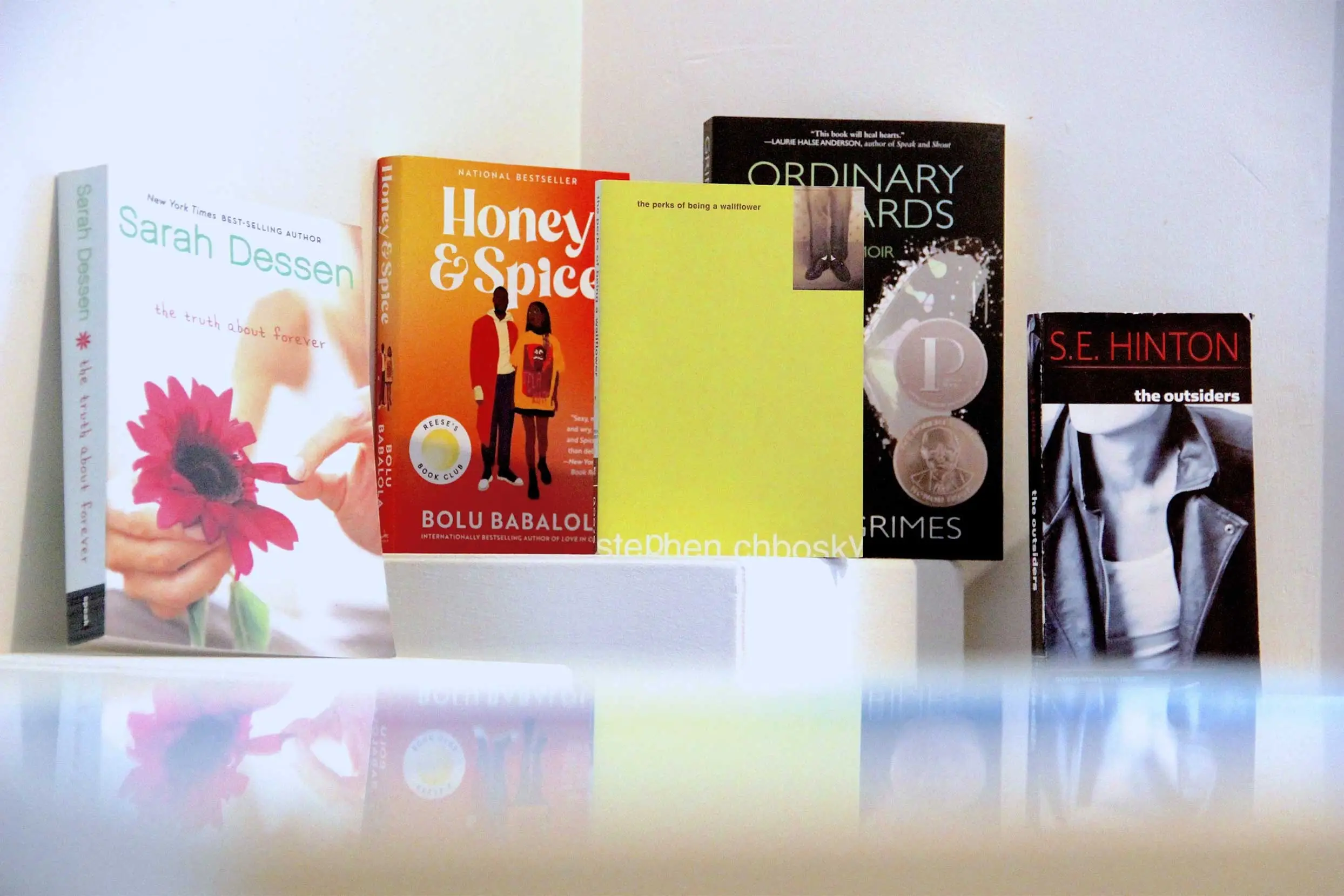

After the two initial edits I conduct myself, I start curating a list of professional editors and advanced readers (usually people in my life who love reading and whose opinions I value). Because I’m self-published and will most likely continue self-publishing, I’m able to choose my editors.

All editors provide holistic feedback, although some focus more intensely on certain aspects of the book. With “The Last of the Mentally Ill,” I hired several Black mental health professionals as editors so I could include their perspective on the book’s Black characters and mental illness theme. My next novel has a leftist sex worker character, so I plan to interview leftist sex workers during my research phase and hire them to edit the first draft.

For me, 10 is the ideal number of people to review a novel before it is published. 10 is a round number we can easily think of in terms of percentage. 10 feels like enough people to sample a general audience of readers. Any more, and the amount of feedback could become overwhelming.

The editors’ feedback includes comments, critiques and suggestions. I normally agree with most of their points. When I see a suggested change I don’t agree with, I begin a mental process where the use of 10 editors has sometimes been invaluable.

First I think about the content they are pushing me to edit, and I ask myself how important it is to the book, as well as how emotionally attached I am. If I make this change, will the book retain the qualities that define it? If they want me to cut a line, how much joy did I feel when I wrote that line?

If I find myself easily emotionally relinquishing the original words or plot point, I make the recommended edit immediately. This outcome is the norm. Because of my background working with editors as part of my content/journalism day job, I don’t get too attached to most of my words. I think this attitude is healthy, and it makes me pleasant to work with.

When I strongly disagree with the editor and decide I don’t want to make the change, I leave a polite comment explaining my reasoning. If the editor doesn’t feel strongly, they’ll leave me be and move on. If they insist that ignoring their edit could severely limit the book’s potential, we will respectfully debate until we reach a compromise.

These debates have been rare but consequential. While reviewing editor feedback on, “The Last of the Mentally Ill,” I saw a comment saying the beginning of the book was too slow. Initially I was hesitant to take action. I thought the beginning had appropriate pacing that thoroughly fleshed out Chester’s mindset. I worried that cutting sections would limit his development as a character.

As I simultaneously reviewed notes from my 10 editors, however, I noticed that more than five of them said I should speed up the pacing of the book’s first chapter by making a series of small cuts. Majority ruled. I made the cuts. A few online reviewers have still argued the first chapter is a bit too slow, but I think this opinion would be far more frequent had I not listened to my editors.

After months of editing rounds based on feedback, I do a final edit myself. Then it’s time to commence the tedious but rewarding process of self-publishing.