As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

TLDR

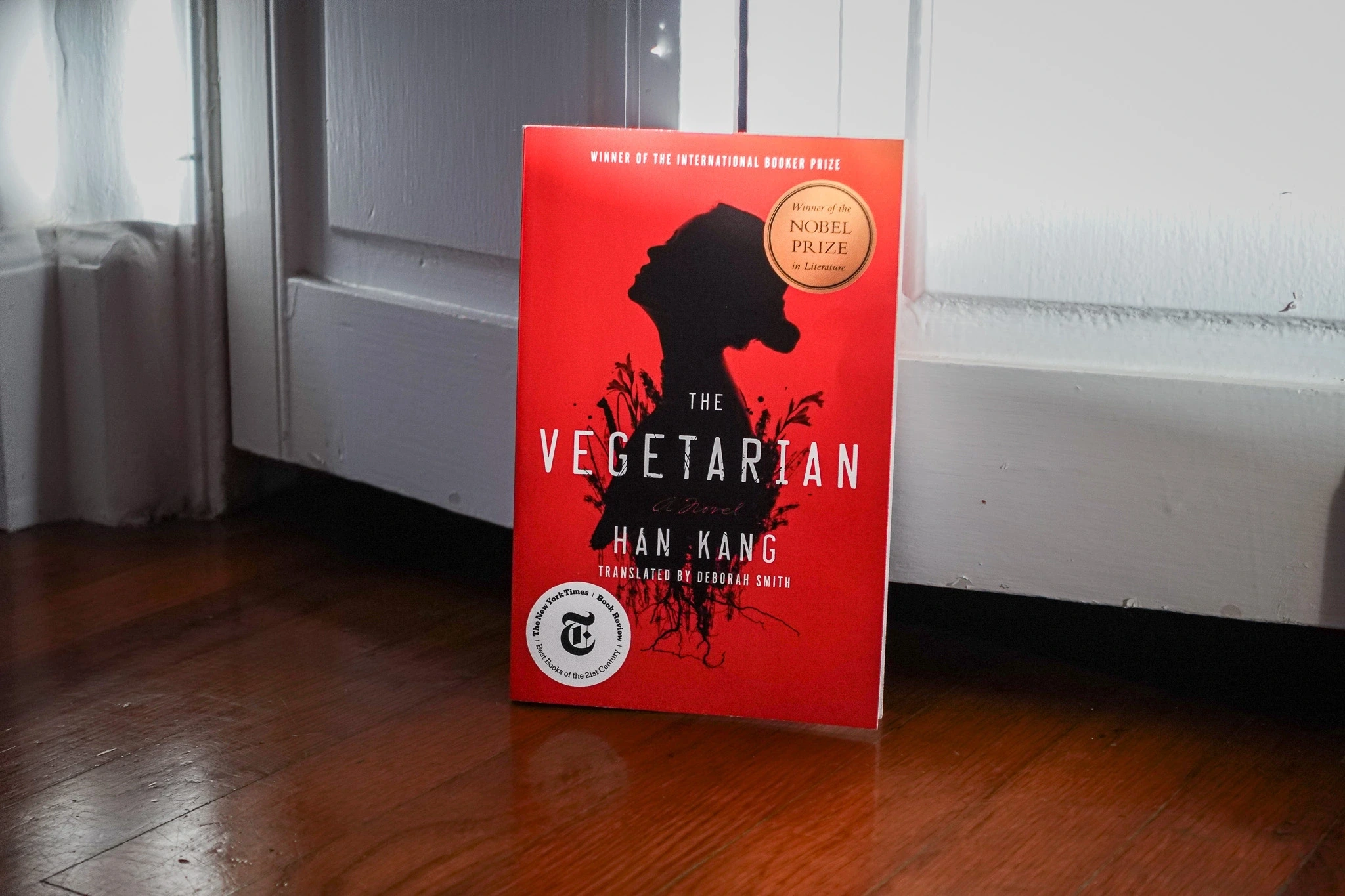

“The Vegetarian” by Han Kang is a novel exploring what happens when a woman chooses to subvert the acceptable parameters of a patriarchal society and the fallout that occurs in her wider family. Containing some surrealist elements, the book is set in South Korea and is based on the 1997 short story “The Fruit of My Woman” by the same author.

The novel tells the story of Yeong-hye, a young wife living in modern-day Seoul and working as a part-time graphic artist. One day Yeoung-hye wakes up from a violent, bloody nightmare about human cruelty to announce that she is to stop eating meat. Whilst this decision may sound reasonable enough, her choice comes to have devastating consequences for her personal and family life, particularly her marriage.

It can sometimes be difficult to translate stories exploring a society outside of the accepted western canon of much of contemporary literature, and often the dialogue can be particularly tricky to translate.

So, how did Han Kang manage to portray such an unusual premise and extend what started out as a short story into a full-length novel, going on to win the prestigious International Booker Prize? Let’s explore.

‘The Vegetarian’ Summary: A Three-Act Story About a Woman Subverting Societal Expectations

The book is written in a three-part structure:

- The Vegetarian

- Mongolian Mark

- Flaming Trees

The three distinct but connected sections don’t have separate chapters, merely a large gap where one idea ends and another begins. Interestingly, the sections are all pretty much the same length, around sixty pages long, making the whole book under two hundred pages in length.

Part 1: ‘The Vegetarian’

The first part of the book, subtitled “The Vegetarian,”’ is narrated in first-person by Yeong-hye’s husband, simply referenced as Mr. Cheong. This honorific is the first indicator that he garners more respect in Korean culture due to his ‘Mr.’ designation, whereas his wife is referred to by her first name throughout.

The first part of the book is particularly engaging, which sees Mr. Cheong considering his wife to be “completely unremarkable in any way.” He explains that he wasn’t even attracted to her when he first met her. He appears to wish to live a conventional and unremarkable life and sees his wife as fitting nicely into this vision. It is clear that she has no agency to disrupt this generally accepted state of affairs.

After several years of marriage, however, Mr. Cheong wakes up to find his wife disposing of all meat products in their freezer. Demanding an explanation for her actions, she vaguely explains about her bloody dream.

The situation deteriorates, with Mr. Cheong calling in the help of his wife’s family when he notices her growing thinner and hardly eating at all. After continually refusing to eat, her husband and family stage an intervention, with her father convincing Yeong-hye’s brother-in-law and brother to hold her whilst he force feeds her meat, leading her to take matters into her own hands and cut her wrists with a knife. This scene of the book held connotations of the practice of force-feeding seen in the earlier feminist movements, and shows the violence Yeong-hye’s family will inflict to force her to conform.

In another example of Mr. Cheong’s willingness to resort to violence, he forces his wife to have sex with him, something which sends her into an almost catatonic state.

Part 2: ‘Mongolian Mark’

The second section of the novel, “Mongolian Mark,” switches to observe Yeong-hye’s brother-in-law who is a failing video artist. Attracted to Yeong-hye, who has now been served divorce papers by her husband, he visits her and convinces her to model for him. He has been attracted to her for a while. His part of the story shows how he views Yeong-hye through the male gaze, wanting to film her and violating her in a different way to her husband.

When his wife, Yeong-hye’s sister, discovers what he has been doing, she calls the emergency services, believing both of them to be mentally unstable. This event leads him to consider throwing himself from the balcony. The disturbing attitude toward acts of subversive behavior as instances of mental breakdown is rife within this novel.

Part 3: ‘Flaming Trees’

Finally, in part three, entitled “Flaming Trees,” the story is picked up by Yeong-hye’s sister, who is now the only family member to support her following her mental and physical decline. Having now also separated from her husband, she attempts to take care of both her sister and her son.

Yeong-hye is living in a psychiatric unit and is now refusing to eat at all, beginning to behave more and more plant-like, introducing a surrealist element to the book. It is difficult to ascertain whether her wish to become at one with the natural world is a part of her own mental collapse and depression at the confinement of her choices as a woman, or whether she truly wishes to become at one with nature.

The book is a fascinating exploration of humanity and innocence. Of the choices we make and the ways in which society and culture attempt to force us to conform. Yeong-hye’s decision to stop eating meat sets off a subversive and rebellious act of autonomy that tears the precarious structure of her family apart, pushing them each to try to assert their control over both her body and mind.

Books Like ‘The Vegetarian’

‘Concerning My Daughter’ by Kim Hye-jin

Also set in South Korea, this contemporary novel similarly explores Korean society and the ways in which women garner respect only when they live within the accepted cultural norms.

At The Rauch Review, we care deeply about being transparent and earning your trust. These articles explain why and how we created our unique methodology for reviewing books and other storytelling mediums.

Audience and Genre: Feminist Literary Fiction with a Touch of Eco-Literature and the Supernatural

Although “The Vegetarian” will appeal to fans of feminist literature, particularly titles exploring Korean culture, it spans a larger demographic due to its unusual structure and the glimmers of the supernatural. Through Yeong-hye’s violent, bloody dreams, we see the inner conflict and turmoil of her mind. We experience her disgust of human cruelty and her wish to become part of nature. In this way, the book also works as a comment on the human destruction of the natural environment.

It is likely that women with an interest in the controlling aspects of patriarchal societies will find this book a fascinating study, whilst perhaps readers of a highly sensitive nature or readers who agree with the need for tight familial structures may find it disturbing. It may also be triggering for some readers due to the incidences of violence and suicidal references.

These potentially triggering elements may explain some of the mixed reviews that appear for the novel on sites such as Goodreads and Amazon. Whilst Korean and Asian literature appears to be experiencing a growing popularity with literary fiction enthusiasts, the book is perhaps not the most digestible, plot-heavy novel. Those who would perhaps most enjoy the book then would likely be readers who enjoy a novel that explores character and theme over storyline.

Perspective: Three-Part Structure, Three Narratives

The book’s perspectives are difficult to define. Though many novelists choose to write books from several different perspectives, they are not usually based around one central character’s story while not showing the perspective of that character.

The first section of the book is told from the first-person viewpoint of Mr. Cheong, relaying the story in the past tense. Kang wrote this perspective primarily because the book is based on her short story, “The Fruit of My Woman.” This section also has some interspersed dream recollections of Yeong-hye, indicated by italics and which is written in stream of consciousness style and appears rambling, like somebody who is unravelling, likely to indicate the spiralling into mental instability of the character.

This is by far the strongest section of the book and the most convincing voice. Though Mr. Cheong is dislikable, he is believable. It is an interesting choice to situate the story of his wife’s unraveling from his viewpoint, particularly in a book that feels like a feminist commentary on society, marriage and control.

The second and third sections of the book are unusually told from other family members, still in the past tense but in third-person narration, whilst still surrounding the events in Yeong-hye’s life. It would have perhaps been more interesting to have a section from Yeong-hye herself. However, it can be appreciated that Kang’s choice of narrative voices within the book added to the sense that the central protagonist really has no voice. It also added to the understanding that her family and society as a whole would likely view her subversive behaviour to be a sign of her unravelling mental health, rather than a personal choice.

Three Cs: Compelling, Clear, Concise

Editorial Note: We believe these three factors are important for evaluating general writing quality across every aspect of the book. Before you get into further analysis, here’s a quick breakdown to clarify how we’re using these words:

- Compelling: Does the author consistently write in a way that would make most readers emotionally invested in the book’s content?

- Clear: Are most sentences and parts of the book easy enough to read and understand?

- Concise: Are there sections or many sentences that could be cut? Does the book have pacing problems?

Compelling: You Will Be Rooting for Yeong-hye

I believe that the voice of Mr. Cheong makes it easy to care about his wife and not himself. Despite him controlling the narrative within the first part of the book, we see him as narcissistic, only caring about controlling his marriage and his wife, worrying more about how her behavior looks in front of other people such as his boss when she refuses to eat meat or wear a bra. His violent act toward her adds to the distaste we feel for him.

Although it may at times be difficult (coming from a westernized society) to fully understand why Yeong-hye’s choice to stop eating meat causes such a big issue for her husband and family, readers will naturally feel a genuine empathy for her attempting to take control of the only area of her life in which she feels she can. It was easy to root for her and to wish that her husband could support her decisions and work with her to resolve her unhappiness.

Clear: Written in a Simple, Succinct Prose

Despite the serious and multi-layered meanings of the novel, it is surprisingly easy to read. Often books that win such prestigious prizes can be written in a rather dense, impenetrable prose. “The Vegetarian” happily bucks this trend, written in a short, clipped, easy prose, making it a short read. The three sections, though working from one central idea, could be read as three separate and distinct short stories.

Whilst Yeong-hye’s predicament is succinctly written, the book does not suffer for lack of emotion. We are deeply invested in her story, whilst being able to appreciate the literary merit of Kang’s delivery. She is clearly a novelist who works well with language. I suspect that her tight prose style requires extensive editing to create only the bare bones of what needs to be said.

Whilst I wouldn’t say there were plot-holes within the text, I did feel that the three-part structure takes you out of the initial story somewhat. As previously stated, Yeong-hye’s own voice would have been interesting to hear. The second and third parts of the novel were less interesting. I was unsure of Kang’s choices to set out the book in this way.

Concise: No Superfluous Words

I don’t think the author could have improved the reading experience of this novel by cutting sections. Although, as I have stated previously, I am unsure of her choices of narrators for these. A novel of a similar length but just extending the first section may have also worked, although I suspect that this would have resulted in a shorter novella.

As stated above, the three sections are around sixty pages in length, with a page typically coming in at around three hundred words in length. The book in total is one hundred and eighty five pages in total. It could be said that the three sections, though working from the same story, can be considered as three short novellas within one book. Some critics have call the entire book a novella.

The novel sits very much in relation to other Korean and also Japanese translated literature I have read in its short structure. This is a style and feature I personally enjoy as a reader, although I know it is not for everyone. The prose style is short and succinct, and there is little in the way of ‘fluff’ or superfluous, descriptive prose. As a reader, I appreciate this brevity. However, readers preferring pretty sentences and longer descriptions of setting, place and emotions may not be a fan.

Similarly, the pacing of the novel felt right. No points were belaboured. We are introduced to the Cheong’s marriage so far, Yeong-hye’s seemingly sudden change of personality through her cutting out of meat, and her husband’s increasing irritation at the situation.

There can sometimes be disparity in dialogue and sentence structure within translated literature. However, despite the book being translated and the story containing references to Korean culture, it was not difficult to understand. The ideas of control and power structures felt universal.

Character Development: The Characters Are Developed… to a Point

The author developed the characters to a point. Mr. Cheong moves through the novel as a baffled, bewildered young husband at the start, to a controlling, increasingly frustrated and angry man wishing to return his wife to his control by the end of the first section.

Mr. Cheong is something of an unsympathetic narrator of his wife’s experience. He represents damaging gender norms in his refusal to accept his wife’s longing for a different life. He simply views her outburst as a form of feminine, romantic idealism, considering himself in opposition as an ideal realist.

The two most important events that heighten the reader’s disgust of Mr. Cheong and side with his wife are, firstly, the force-feeding incident he induces by taking her to her family to stage an intervention. Secondly, and more disturbingly, Mr Cheong takes out his growing frustrations with his wife’s behavior by forcing her to have sex with him. This assault pushes her into an almost catatonic state and represents further his wish to reestablish his control over his wife. She in turn begins to stop wearing a bra, a further symbol of her growing resistance to both the constraints of her femininity and her husband’s wishes. Her behavior becomes increasingly a defiance of the patriarchal structure of marriage and her role within it.

Yeong-hye in turn is seen to become increasingly unresponsive. Her initial wish to adopt vegetarianism due to a dream is portrayed as unusual and an act of rebellion. Her later development, however, casts doubt on her mental stability and is portrayed as less an act of rebellion than a descent into mental breakdown.

Moving between narrators showed the skill of Kang to write from different character points of view. The brother-in-law and sister’s voices are written totally differently to Mr. Cheong and are in third-person narration. None of the characters truly understand why Yeong-hye is acting the way she is. Kang shows them approaching her experience through different eyes and voices. The similarity is that they all wish to exercise control over her in some way.

Story: A Unique Perspective

Throughout the narrative, we witness some of society’s most inflexible structures: the ways in which we (particularly women) are expected to behave, and the disintegration of the family. The book reveals closely linked frictions between desire and detachment.

The book is sensual and alluring, provocative and violent, engorged with a potency of startling images and even more startling questions. Even Yeong-hye’s dreams appear as dense, bloody transformations with seductive descriptions of flower-painted bodies in a flux of transformation. Despite her having no formal ‘voice’ within the novel, we nonetheless get a sense of her inner landscape.

The book felt totally original. The plot sounds quite bizarre, and it is. But it also felt like Kang wanted to pursue the idea of power structures and lack of agency for women within them. The ‘plot’ is not difficult to pursue. Like much literary fiction, it is not a plot-heavy novel.

The story was engaging. Readers will be interested to get to the end. Some may feel a little unsatisfied at the end, though. The nature of the story does not allow for a neat ending.

*SPOILER WARNING*

The ending of the final section of the book sees Yeong-hye confined to a mental institution by her sister, who feels guilty at not being able to care for her by herself. As she attends the facility, she witnesses the staff attempting to force feed Yeong-hye, and tries to intervene, forcing the doctor to quickly remove the feeding tube and subsequently causing a rupture, needing urgent medical attention from the main hospital.

As the two sisters ride the ambulance together, Yeong-hye close to death, her sister begins to speak of the dreams she too has. It is clear from this final part of the book that she is trying to make sense of her sister’s decision to stop eating, confessing that she, too, has often wished to step out of the accepted roles she has played: daughter, wife, mother. As she confesses to Yeong-hye, she realizes that they aren’t all that different, and that it would be an easy step for her to allow herself to let go and unravel.

By allowing for the final section of the book to end with just the two sisters, the final scene allows for a recognition that the patriarchal society has meant that, for women, they must either conform or end up as Yeong-hye has: mentally unstable and close to death, deserted by her husband and alone. Her sister In-hye, meanwhile, is also alone as a single mother and the sole family member who still cares for Yeong-hye.

The ending represents the resilience of Ing-hye and the difficulties of oppression, supplication and power within a restrictive culture.

Prose Style: Simple and Engaging

The prose style felt aligned with other Korean literature in its simple and fluid narrative. It was easy to follow and engaging. When it did wander into more descriptive prose, it was done succinctly and well. It fitted the story in its delivery.

The narrative voice of the characters allows for Yeong-hye to be shown to us through their varying eyes and viewpoints, and the author resists ‘telling’ the reader what is happening or what they should think about the characters or storyline.

The prose style is very much in line with what one would expect from a book of literary fiction and may not be the best choice for readers more familiar with plot-heavy stories.

Dialogue: Convincing

In translated literature, it is often the case that dialogue can feel a little less convincing. However in “The Vegetarian,” the translator worked hard to mitigate this potential shortcoming. Sometimes there are clunkier dialogue exchanges than may be seen in non-translated works, but it still works well. We can identify Yeong-hye’s growing rebellious nature through her short answers to her husband’s questions, as well as his growing annoyance with her answers.

Impressively, the dialogue in the second and third sections is also clear, despite the change of narrative voices.

Setting: Contemporary South Korea and the Domestic Sphere

Setting her novel in contemporary South Korea, Kang has taken advantage of the recognized social structures purporting that patriarchal control and casual male violence within the domestic sphere poses a threat to women. However, such violence in women poses a danger to themselves, as seen by Yeong-hye’s attempts to cut herself as well as to starve her body as an act of rebellion against her husband’s control.

The translation of the book into English allows for the setting to be introduced to a wider audience, and encourages the reader unfamiliar with the importance of family structure to see the bigger picture. As “Concerning My Daughter” author Kim Hye-jin told Korean Literature Now, “The most powerful unit of solidarity in Korean society is the family.”

In accordance with other South Korean female authors, this book examines the space of the apartment as a shaping factor within the domestic sphere, exploring links between South Korea’s industrialisation and capitalist conformity. Apartment blocks are predominant in Seoul, particularly amongst young working couples such as featured within this novel, due partly due to urban housing policy making this housing a convenient choice for accessing work and amenities for families and couples. As such, many Korean authors situate their domestic stories within this setting.

Rhetoric: A Feminist Representation of Control

The author portrays the plight of Yeong-hye and her marriage to Mr. Cheong well, as well as her place within the family structure from a feminist perspective. Because she has other characters deliver the narrative, she allows for a rounded viewpoint of Yeong-hye’s behavior.

This narrative dynamic is a clever act on the author’s part. If the book had been written from the wife’s perspective only, it may have been viewed as a more simple feminist discussion on control and lack of autonomy. By allowing us to see through the other character’s eyes, we can ascertain how important the idea of family values and the image seen by outsiders is to Korean society.

Cultural and Political Significance: Feminist Ideology, the Male Gaze and the Control of Women’s Bodies

The ideas within Kang’s novel, as an extension of her earlier short story, can also be read in the eco-literature space in their representations between humans and the natural world. Not only does Yeong-hye choose to give up meat in an act of rebellion against the violence of humanity, she begins to feel herself more akin to that of plant-life, exploring the relationship between humans and the natural world.

Kang’s choice to explore the control of women’s bodies within a powerful patriarchal structure is relevant to modern audiences familiar with increasingly disturbing political rhetoric. Though set in the culture of South Korea, her narrative poses worrying concerns of how such power structures can become dangerous spaces for women’s autonomy. Her links with eco-literary devices also feel relevant in an age of increasing concern over the violence of environmental destruction.

According to some critics, Korean literature itself is having a moment, with English-speaking audiences continually seeking out novels such as “The Vegetarian”. The sparse prose in such works, as well as the general aesthetic these books convey, appears to signify a trend in this regard, as can be seen in the bestseller lists in recent years.

Readers have pointed to not only Korean but also Japanese literature as particularly resonant in their themes of isolation, particularly of the younger generation, women even more so. Viewing such novels through a historical lens has also been cited, with Korea once being seen as one of the poorest nations in the world, which has now risen to one of the richest. This all taking place within the space of one generation again appears to link to industrialisation and commercialism, leading more young families to choose city living.

There also appears to be a trend of Asian short stories becoming longer novels, with other recent examples such as “Pachinko” by Min Jin Lee, which started out as a series of interconnected short stories. The Asian novel aesthetic appears to suit this form, covering surprisingly large themes within this format. Rather than publishers actively seeking this method of publishing however, it is likely that many authors attempt to write in this shorter form to begin with, with publishers, recognising the interest in recent years for Asian literature, wishing to capitalise on a writer’s existing work.

Book Aesthetic: Feathers, Scars and Roots, Depending on the Edition

The different editions of the novel vary between showing a wing of feathers, likely indicating the way Yeong-hye is often seen as a delicate creature, aligning herself with the natural world; a scarred woman’s torso, likely referencing the violence in the book, both from her family and her at her own hand; and an illustration of a woman’s head with roots emerging from her neck, indicating her wish to turn into a plant. In this way, the book is targeting an audience more familiar with the feminist eco-literature genre.

Critiquing the Critics: Popular with Literary Critics, Controversial Among Academics

Critic reviews of Han Kang’s “The Vegetarian” are generally positive, tending to praise the way the author challenges the reader with an unsettling and thought-provoking view of South Korean culture. In particular, politically centrist periodicals and review sites tend toward high praise of the novel’s themes and of Kang’s overall writing style and structure. The Guardian referenced the book’s “bracing, visceral, system-shocking addition to the Anglophone reader’s diet,” whilst The New York Times suggested that “All the trigger warnings on earth cannot prepare a reader for the traumas” of the book. Whilst many of the established literary reviewers, not to mention The Booker Prize judges, were busily heaping praise on Han Kang’s viscerally shocking novel however, the New York Review of Books journalist Tim Parks claimed himself mystified that the novel had won the prestigious prize, suggesting that the prose lacked elegance.

Translation Controversy

Something that came to my attention whilst researching the novel, however, was the controversy around its English translator, Deborah Smith. Shortly following Parks’ comments on the English translation of the novel leaving him less than impressed, an academic named Charse Yun writing for the Korean Expose joined in the criticism of the novel in its translated form.

Following up on complaints raised by his students, according to Yun, almost 11% of the first part of the novel was mistranslated, with another almost 6% of the original text omitted from just this first section of the book.

Yun did acknowledge that even the best of translations contain small errors, but his findings included what he considered more glaring mistranslations, including the opening line of the book and the stylistic differences in the two women’s versions. He drew a comparison of the differences between Raymond Carver’s precise prose and the elaborate writing of someone like Charles Dickens.

Responding to the criticism, translator Deborah Smith, who had only begun learning Korean three years prior, stated that Yun was entirely right in his assumption of her version creating a completely different book. She asserted that there was no such thing as a truly literal translation, in that there are no two languages with matching grammar, vocabulary or punctuation. Translation of a text, according to Smith, is always a creative project.

It’s an interesting consideration, and one which the original author appeared to be happy with, working closely with her translator to bring the story to the English-speaking market. But it does throw into question whether we need, as readers, to be cautious when accessing translated texts, recognizing that our understanding and interpretations of them may not be what the original author fully intended.

A Divide Within Consumer Reviews

Among general reviewers of the novel, there appears to be a distinct and stark split. Those who enjoyed the novel tended toward readers who appreciated literary fiction, especially Asian literature. They recognized the importance of the themes and were appreciative and reflective on the shocking nature of the narrative.

However, a large number of the general readership appeared to find the book too ‘literary,’ claiming that it intellectualized what was essentially a story about some pretty disagreeable men and two sisters with whom they could not associate. As I found myself, they also struggled with the fact that the story was not told from the point of view of the central character herself, Yeong-hye, and found this a frustrating element to the book.

Reviewer’s Personal Opinion: A Wholly Unique, Fascinating Feminist Discussion on Autonomy and Control

As a regular reader and researcher of feminist literature, I found the book an interesting and unique exploration of women’s power — or lack of — within a strict patriarchal structure.

Although not a huge fan of the supernatural, the narrative devices used by the author allow for the idea that Yeong-hye begins to see herself as merging with the natural world, either as a further sign of her defiance against the labeling of society, or a symptom of her descent into mental breakdown. I found this ambiguity an interesting concept to consider when reading stories of women’s choices and claiming back their own power.

One downfall of the book could be said to be the lack of Yeong-hye’s own voice within the narrative, other than her recollection of the fevered and bloody dreams she has, which are indicated in italiacs. I would have liked to hear from her perspective, and perhaps this narrative would have worked well intermingled with her husband or other family members’ voices.

I can get on board, though, with the idea that the author likely chose this way of writing the book to show how women’s voices are often disregarded. This theme reminded me of older narratives in which women’s depression or other mental health conditions have been disregarded as hysterical, feminine issues. It also allowed for the slight magical realism element of the text, surreal moments that felt a little like a fever dream and allowed for the reader to sense that Yeong-hye was unraveling before the eyes of her family and spouse.

It also seems clear that the first part of the book worked perfectly as a standalone short story as it was originally intended. Kang wrote “The Fruit of My Woman” in 1997, a direct precursor to “The Vegetarian,” which appeared as a novel in 2007. Both feature a married couple whose life is shattered when the wife begins to undergo some kind of transformation. The short story, which can still be found on Granta, contains much more in the way of magical realism, whilst “The Vegetarian” is more rooted in reality. Both stories feature the wife as a woman intent on turning into a fruit bearing tree, which in the novel is more understood by her family as a sign of her mental illness. Whilst in the short story version, the woman literally becomes a plant.

The supernatural elements of the story are related to Kafka-esque motifs, and the translator of the novel into English, Deborah Smith, has suggested an influence of Korean Buddhism within the text, with the hint of violence as an inherent trait within humans.

Conclusion: A Unique and Disturbing Examination of a Woman’s Lack of Control

The book remains an important, fascinating exploration of feminist ideology and the idea of power and control. As our political structures undergo more dystopian ideologies and dialogue around the control of women’s bodies, I find that this book gains a new momentum.

Although set in a more patriarchal marriage structure than many readers will be familiar with, I think it is easy to see how Han Kang’s novel can relate to the current discussions over autonomy and control.

I have awarded the book a 4.5 as I believe it is an important addition to the feminist canon. My only reservation is that we do not hear from the central protagonist herself. This omission is likely deliberate on the part of the author, but it would have made a great study on feminine power even more interesting. I also feel that the three-part structure, whilst an interesting literary device, felt like an unnecessary addition. The first part of the book is by far the most engaging to read.

Buying and Rental Options

E-Commerce Text and Audio Purchases

E-Commerce Audio Only

Physical Location Purchase and Rental Options

“The Vegetarian” is available from most major retailers and is particularly popular in independent bookstores, where it may be placed in the literary fiction or feminist fiction aisles. It is often found beside titles such as “Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982” by Cho Nam-Joo and “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

Editorial Note: Read our full review of “The Yellow Wallpaper” here.

Digital Rental Options

Many public libraries hold digital copies of “The Vegetarian,” although it is still popular and as such, readers may need to be prepared to wait a while for a hold on this title. Digital copies can usually be obtained via an app such as Libby.

Get recommendations on hidden gems from emerging authors, as well as lesser-known titles from literary legends.