As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

TLDR

Mohammed El Kurd has been an activist, poet and journalist for as long as I can remember, doing interviews and bringing attention to his birthplace of Sheikh Jarrah in East Jerusalem. He and his twin sister Muna have been internationally recognized activists, speaking out about the dispossession of their homes by Israeli settlers since 2009, exactly at the time when they were kicked out of their homes when they were 11. Their family was chased out of Haifa in 1948 and since then has been pushed out of their homes multiple times. His interviews, recordings, and discussions on the violence against Palestinian people has made him a recognized journalist.

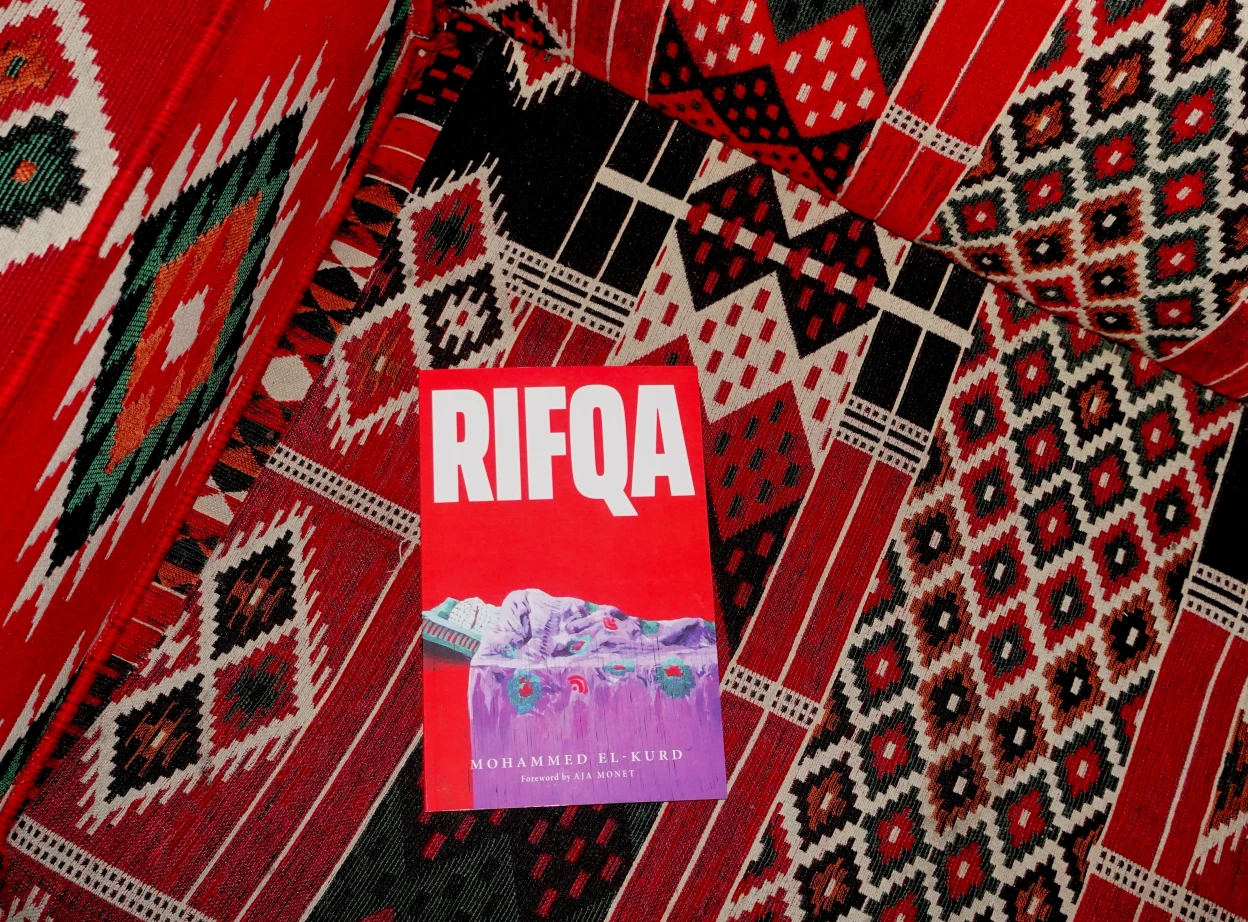

El Kurd named his poetry collection “Rifqa” (Haymarket Books, 2021) after his grandmother, Rifqa El Kurd, who stood strong against the Israeli occupation. Her refusal to be a “humanitarian case” has been a part of El Kurd’s explanation that Palestinians have constantly humanized themselves for the world to care.

This message is constant in “Rifqa,” a collection of approximately 100-pages with 30 individual poems that argue Palestinians should not have to prove they are human for the continued occupation, violence and dispossession of their people to stop. As El Kurd says in his poem, “Bulldozers Undoing God,” “A soldier as old as a leaf born yesterday / pulls a trigger on a woman older than his heritage.” He finishes the poem with: “Here, every footstep is a grave / every grandmother is a Jerusalem.”

Through free verse, prose poetry and raw language, El Kurd shares his emotions with readers in a way that makes us reflect on the West and its continued work to erase a whole people’s narrative.

October 7 and the continued tensions in Palestine currently beg us to return to El Kurd’s language. What other voice to hear but the voices the world wants to deny?

Here El Kurd writes in “Rifqa” about when his family was pushed out of Haifa: “My grandmother —Rifqa — / was chased away from the city, / leaving behind / the vine of roses in the front yard. / Sometime when youth was / more than just yearning, / She left poetry. / what I write is an almost. / I write an attempt.”

Poetry is not only a claiming narrative here, but a yearning, a wish. Poetry is on the brink. With El Kurd’s language, we are asked to look over the edge and truly see.

El Kurd: “I cried—not for the house / but for the memories I could have had inside it.”

‘Rifqa’ Summary and Analysis: A Testimony to Palestinian Narrative and Family History

“Rifqa” is a poetry collection El Kurd has written with open wounds and, at the same time, powerful claims to the Palestinian narrative.

The 30 poems are separated into four parts. Though the stories of displacement, family history and yearning thread throughout all the poems, I felt that the four parts could represent:

- home in Jerusalem and family history

- demanding true Palestinian representation

- life in the States and seeing Palestine from the West side of the world

- a declaration for Palestinians

El Kurd echoes many writers and singers throughout his work — namely Mahmoud Darwish, Umm Kalthoum, Audre Lorde, Malcolm X, even Nicki Minaj. As a reader, I feel I am moving from one space to another as El Kurd fans the focus from Palestine to his experiences in Atlanta, where he studied at Savannah College of Art & Design (SCAD).

Everywhere the themes of colonialism, art and displacement follow him and form a lens on which we see Atlanta, a city of deep history and powerful Black narratives. It’s hard not to see colonialism everywhere, yet he learns how to command the language to speak about pain.

From “Laugh”:

“Jerusalem taught me resilience. Atlanta taught me a different kind. I can now bring the funeral to the podium and laugh. My grandmother taught me if we don’t laugh, we cry. Atlanta knew that.”

One of the themes intertwined in this collection is the idea that Palestinians have had to prove their humanity to be worthy of saving.

From “Autobiography:”

“I used to pimp my pain / pawning soldiers for my pleasure / It was playtime for the twins / Used to pimp my pain / Now I merely exploit it / I’ve identified the problem ashes where should be dust…” He ends the poem: “What does that say about me? This isn’t an epiphany, though / Poems aren’t for that.”

These lines reference El Kurd’s young age at 11 when he was interviewed in East Jerusalem after half of his home was overtaken by settlers. When you watch the video, you can see him and his sister walking around confidently, showing the camera around the narrow alleys between buildings, describing the neighborhood. Young journalists are born. In one shot, El Kurd and his twin sister Muna see a settler and yell, “Settlers, thieves! Leave the houses!” Then they start to run, their young voices laughing and muffled in the camera.

El Kurd knows how to use language, how to “exploit” his pain — but he also argues that this dynamic is part of the problem. Why does one have to exploit their pain to receive basic rights, like freedom, security and safety? As a young kid, that was his “playtime.” Now that he’s older, it seems he’s recognized that the West has demanded their victims play weak and broken to receive recognition. El Kurd refuses to do that. Part of a human’s humanity is dignity.

He also states throughout his collection the function of poetry. It isn’t for epiphanies, as he says in “Autobiography.” The purpose of poetry seems to be different for El Kurd, who declares in “No Poetry in This”: “There is no poetry in suicide and / no poetry in cigarettes.”

In the face of violence and pain, it seems poetry cannot be found in those places. In this way poetry seems synonymous to beauty, but there is no beauty here. Yet, El Kurd writes, poets still “break their lines with threats of triggers.” In this way poetry is an action, even a violent one. Poetry is almost like ammunition, an impulse. Poets can’t help it. And it seems El Kurd finds this sad, in the end, that we must come to poetry at all. If we had peace and basic rights, would poetry be a necessity the way it is now?

El Kurd’s debut collection is a series of raw poems where El Kurd explores the dignity of Palestinians, reflects on his childhood and family history, and tells it how it is. To be erased is not an option for him, is not what his family taught him. As a reader, I can see the yearning in El Kurd’s language, how much he misses his home. He writes: “I have never once felt free anywhere” and “I am but my nostalgia, / my sick homesickness.”

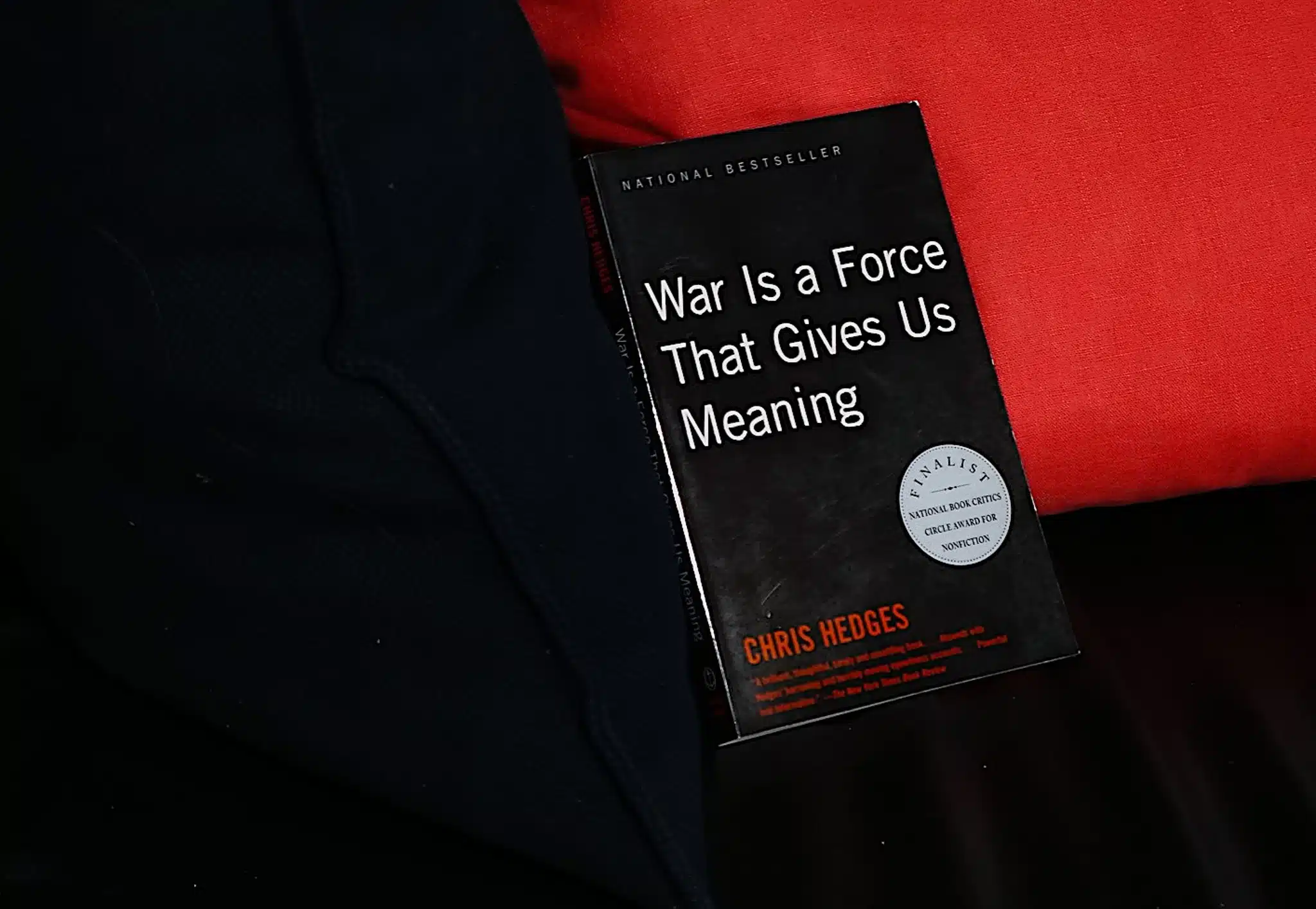

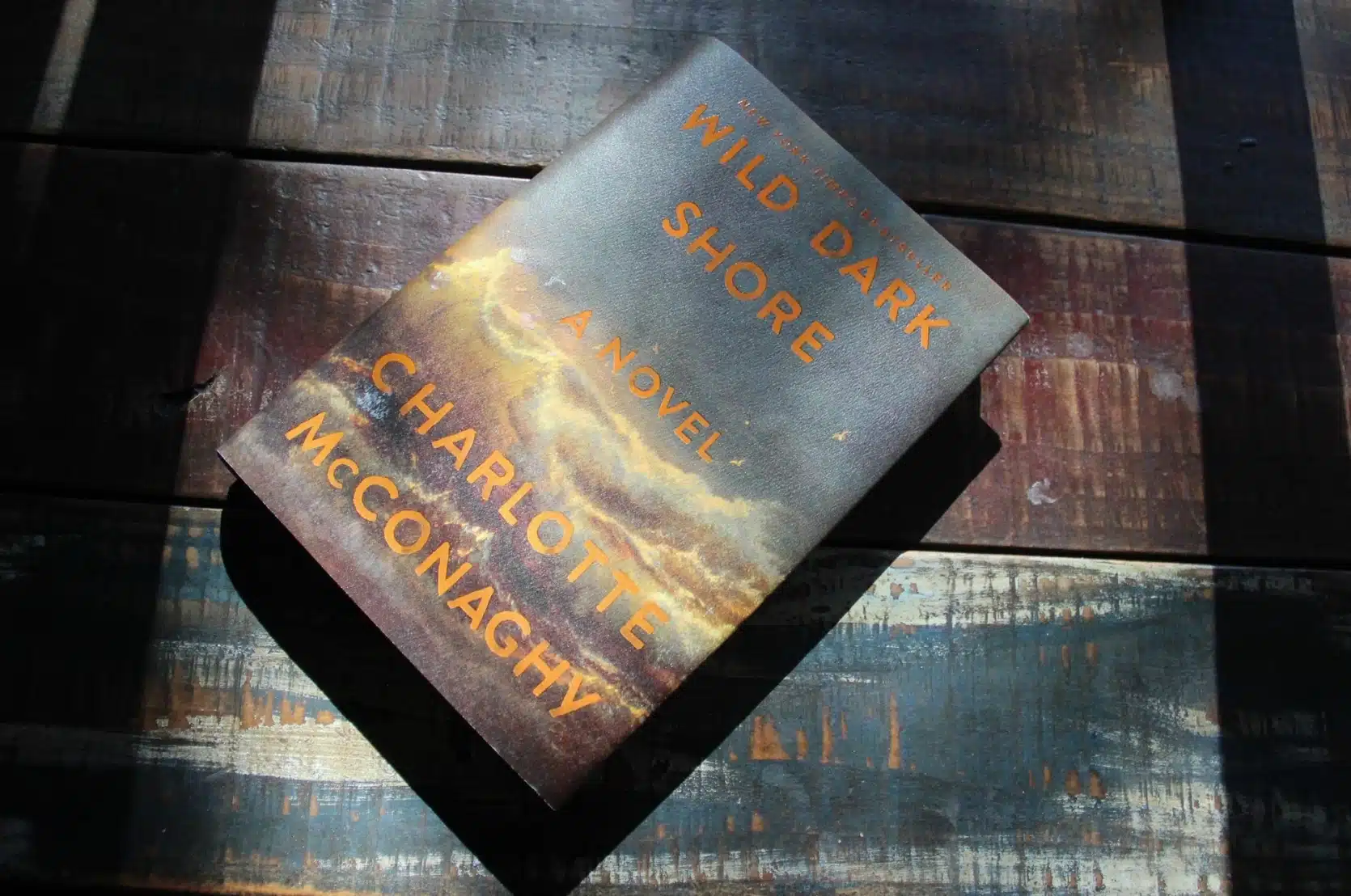

Related Authors and Books

There is an expansive list of Palestinian writers and poets who have constantly been speaking out about Gaza. I’ve only included a limited list here, but encourage readers to consider the many poets who don’t garner as much media attention yet write about Palestine every day:

- “If I Must Die Poetry and Prose” by Refaat Alareer: This text is a crucial read by Alareer, whose poem “If I Must Die,” bled through social media posts when he was killed in an airstrike by Israeli forces on December 6, 2023 in Gaza.

- Fady Joudah’s […] Poems: A 100-page poetry collection by physician and poet Joudah and his thorough declaration of the endurance and resilience of the Palestinian people

- “Unfortunately, It Was Paradise” by Mahmoud Darwish: Darwish is endlessly quoted by El Kurd and also other poets on social media. He was known as Palestine’s national poet.

- “Birthright” by George Abraham: This poetry collection has won several awards namely the 2021 Arab American Book Award in Poetry.

- “19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East” by Naomi Shihab Nye: Deeply loved and treasured, Nye has written about the Middle Eastern and stories of Palestinians that resonate with readers of all ages (she’s written a novel for young adults)

- “Water & Salt” by Lena Khalaf Tuffaha: As an Arab American essayist and and poet, Tuffaha has won several awards for her writing about Palestinian lives and Western language when it comes to writing about Palestinians

- “The Moon That Turns You Back” by Hala Alyan on displacement. As a psychologist and writer, Alyan has garnered awards for her writing and comforting language for those witnessing the genocide and how they can take action.

Editorial Note: Read our review of “The Arsonists’ City,” also by Hala Alyan.

The list can go on and on, as it should. As El Kurd says in an interview with The New Arab: “It’s our obligation to write.”

At The Rauch Review, we care deeply about being transparent and earning your trust. These articles explain why and how we created our unique methodology for reviewing books and other storytelling mediums.

Audience and Genre: Accessible Prose and Perspective for Poetry Lovers

El Kurd’s language is accessible to anyone. He uses free verse and prose poetry, smoothly navigating through the themes of Palestinian dignity, language, family history and his move to Atlanta for school. His prose poems, such as “Why Do You Speak of the Nakba at the Party?,” are conversational and reflective. As he uses pronouns like “we” and “you,” he makes readers feel he is speaking to them.

For most readers, the mission will be to read between the lines and pause on El Kurd’s imagery and metaphors to meditate on his thesis.

Here’s an example from “A Song of Home”:

“I / was dragged into cars and dragged into points of view. / I talked to God but God never wore my shoes.” Here El Kurd tells the story of the many times he was detained for his work. When he says “God never wore my shoes”, there is a feeling that nobody has seen his point of view, never taken his perspective into account.

A lot of El Kurd’s writing is storytelling as much as it is metaphors and imagery, like “Boy Sells Gum at Qalandiyah,” “Rifqa” and “Smuggling Bethlehem.” This pattern makes his poetry a historic account as much as it is a play on language.

For those who understand Arabic and English, they will be delighted to see references to Arab singers and poets, as well as feel the familiarity of reading both languages on the page.

Themes: Yearning, Important Women, Language

Yearning

To yearn for a homeland is a consuming feeling. It’s one that people from the Arab World know often. When I read El Kurd’s words, there is rage and then there is yearning. El Kurd’s poetry can be a love letter to Palestine.

In “Anti-Biography” he writes: “I am but my love for my land, by the way. / I have chosen you, my homeland, in love and in obedience in secret and in public.”

When I read “obedience,” it reminded me a little of prayer, of submitting and persisting for something that is greater than you. It reminds me of a vow you give on your wedding day. The words “in public” could also refer to El Kurd’s public speaking and journalism he’s done for Palestine on national news and at universities like Oxford, Princeton and Harvard.

He writes: “I have never once felt free anywhere / not with the Jordanian passport; / not in Santa Monica, the American Tel Aviv; / not in New York, the American Tel Aviv; not in Tel Aviv, the American Tel Aviv.” Then: “I am but my nostalgia, my homesickness.”

In this way, there is no escape from the prison of homesickness, of yearning to return. Yearning is a sickening feeling. It follows you, like a ghost. And it is raging in this poetry collection. Yearning for a homeland is like yearning for a mother. “I am but obedience to my mother,” he writes in the same poem “Anti-Biography.” Like a mother, Palestine houses, feeds, harvests. Like a mother, it wants its children home.

Important Women

After I read the poetry book a second time, I realized the theme of strong women in El Kurd’s life. Indeed, I often see Palestinian women on TV, speaking to the camera, seeking food for their children. The entire collection is named after his grandmother. El Kurd also mentions his mother several times in the book, talking about her resilience.

In his poem “Three Women,” which is written after Nina Simone’s “Four Women” and Suheir Hammad’s “4:02 pm,” El Kurd talks about three women from different places — Atlanta, Jerusalem and Gaza — and brings them together on the page by way of power and strength.

Women in El Kurd’s poetry collection are not only pillars and holders of history, they are also entire cities. In “Bulldozers Undoing God,” “every grandmother is a Jerusalem,” he writes. An older woman living in Jerusalem can be twice or three times the age of a soldier holding a gun to her.

El Kurd’s twin sister, Muna El Kurd, was at the forefront of the #SaveSheikhJarrah movement where they fought to keep their homes from Israeli settlers in Sheikh Jarrah after the Israeli court ruled that their homes were to be taken.

We learn later in El Kurd’s afterward that his mother was a published poet. He states: “Language is not free.” Indeed, if you’re reading this now, my time to write is at the expense of another.

Language

There are many things to appreciate about El Kurd, but one main thing is his self awareness of what it means to have media attention. In an interview with The Public Source, El Kurd talks about Palestinians being on national TV because they lost entire families. His resistance to engaging with certain media channels to relay his message is part of his wider claim that Palestinians are used as victims to perpetuate the Western narrative. To be seen as humans, Palestinians have to plead or seem innocent. Even innocent children, he argues, must look innocent enough or they garner suspicion from the public on whether they’re worth saving.

This work has led him to talk about having so much media attention and the obligations that come from that. In the same interview he says, “I organize with multiple collectives, and although I operate by myself, I try to always seek opinions from many, many different people when I’m writing or when I’m speaking because I understand that when you get to this place of visibility, your voice is no longer yours.”

El Kurd is self-aware, even in his poetry, about how much poetry can do for us in a time of accelerated genocide. What does poetry do when entire lineages are being massacred? He says: “…the war we’re in is, in fact, and fundamentally, a narrative war. There is a side that is far more equipped militarily and backed, in terms of Western and global support — but this is also a war of consciousness. So, this is the role of unabashed, unapologetic literature.”

Unapologetic literature is written because the narrative has always been Western and capitalist. El Kurd’s words give some encouragement, that at least writing our stories is working to tell our own stories, because nobody is going to tell it for us, and nobody is going to tell it right as we do.

In “Girls in the Refugee Camp,” he writes: “Your ambition is ammunition / bullet-less.”

‘Rifqa’ Poetry Form: Taking Liberties on the Page

El Kurd takes liberties on the page in this collection, writing in free verse, prose, and often including erasure poems that scatter about the page like visual art.

Erasure poems like “WHO LIVES IN SHEIKH JARRAH?” use a New York Times article published in April 2010.

Most of the poems in this collection are free verse. El Kurd uses imagery, metaphors and alliteration. Like “Girls in the Refugee Camp”:

“Soldier

hands you hash

and handcuffs,

hijacks your halves.

You are the prisoner and

you are the cell.”

The alliterations in this poem: hands, hash, handcuffs, hijacks, halves, make way for the final line to resonate so deeply. And for the “you” to be many things – not just the prisoner but also the cell, and also…the list goes on and on.

El Kurd’s style can be characterized by alliterations. “Do I believe in violence?” he writes in “Kroger,” “Well I don’t believe in violation.” The alliterations cause twists and turns within the lines. As readers, we think the line will be about one thing and it is about another.

In this way El Kurd works with metaphors, as people in his collection turn into cities and Palestine itself. What better way to characterize a country but with its people? The “you” is a prisoner, and “you” is also a cell.

Along with his alliteration work, El Kurd also uses repetitions to make statements. “Separation is like / unmaking love/ ungluing names to places / undoing God. A pulling pressure, soldiered: / occupiers occupy her limbs, / untangling a grandmother.” The repetition of “un” feels like an undoing–everything that was in Palestine is undone.

Critiquing the Critics: Justified Praise and Unjustified Antisemitism Accusations

Many critics positively and intensely praise El Kurd’s poetry collection. Los Angeles Review of Books wrote: “El-Kurd pours so much into this collection, in search of that opportunity for laughter, in celebration of those he documents.” On Goodreads, it is given a 4.65 with readers using words like “heartbreaking” “beauty” “the future” and “raw.”

General critics agree El Kurd’s language has “beauty,” as in this review. Readers have studied his words in wonder to understand its many meanings and enter into discussions about Palestinian narratives. One commentator even wrote that El Kurd’s collection should be required reading.

El Kurd’s collection has been so widely reviewed that the ADL wrote a whole article that mentions it. They argue he is anti-semitic and is acting with violence, though they never mention the violence acted upon his family or Palestinians in an accurate light. In one introduction, the article says, “To be sure, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is intensely personal for El-Kurd.” Then: “Nevertheless, his willingness to employ these tropes raises serious concern.” The article seems to be written as if they’re “pointing a finger” rather than truly acknowledging the torture, displacement and continous murder that Palestinians have endured for years.

Work like Rifqa is striking and powerful because it allows for accessibility in a different way that an interview or video does not provide. Poetry asks a reader to sit, to focus only on words, no distractions. Poetry asks readers to invest and to interpret. Poetry asks readers to write. El Kurd’s language is stunning and intimate, bringing Palestine to the readers, so much that we feel a part of it.

If you search “Rifqa,” you will see how much is written about it, how many places it is being sold. You will understand that poetry is not just used to yearn, but to reach for another hand.

Interior Visuals: Play With Space

El Kurd experiments with space in his collection. Some poems are tight, in a prose poem. Others use the space to make a statement.

In “Laugh,” El Kurd writes a prose poem reflecting on Atlanta’s artists funneling creative energy into power, with the backdrop of a city and its complex history. The poem is tight, with barely any space. As a reader, I lean into the poem’s rhythm.

In another poem, the lines don’t stay in one spot. “Amal Hayati” dares us to interpret the spaces while English and Arabic words interact with one another. In the center, a merged identity comes to life. We get Arabic and its translation of the haunting “Keep me / by your side, keep me. / In your heart’s embrace / keep me.”

The title references Umm Kulthum’s song by the same name, but in Arabic. In fact, El Kurd references this Egyptian singer and her iconic songs many times throughout his collection. His references are an accumulation of the artists that have influenced him over time. In “Amal Hayati,” El Kurd fuses music into his poetry.

Exterior Visuals: His Grandmother and Jasmine

There’s more to the cover than what catches the eye at first. The title, dedicated to El Kurd’s grandmother, is in bold letters across the front. We see a man lying under a blanket with patterns of floral and red. His eyes may be closed and he is wearing a keffiyeh on his head. The floral can represent jasmines, which his grandmother, Rifqa, greeted El Kurd with during his visits. Flowers are also an important theme, as Palestine is known to be fertile land, for olives, herbs, and various fruits. The red color on the cover is blaring. It can represent violence, blood, and political tension.

Order and Cohesion: Returning to Palestine

“Rifqa” is separated into four parts, a total of 30 poems. In chronological order we feel that El Kurd starts with Jerusalem, his home, and gradually moves to talk about his love for his homeland after he moves to the States. He reflects on Palestine everywhere, even when he isn’t in the country. Readers get to see El Kurd’s influences in Arabic and English, from the Arab World and the States. In this way I believe the parts are broken accordingly:

- home in Jerusalem and family history

- demanding true Palestinian representation

- life in the States and seeing Palestine from the West side of the world

- a declaration for Palestinians

Personal Opinion About ‘Rifqa’: The Only Plea I’ll Make Is Read This Book

I’m writing this review two days after the US and Israel have hit Iran. Yesterday I attended an Iranian wedding. I’m writing this at a cafe while the Middle East is rupturing. All I can think is: what do I do with myself, with my art, when people who share my blood are dying? Maybe it isn’t about art anymore. The art is living to speak about it, to help. Living is an art, as I’ve seen Palestinians move from north to south, then north again.

El Kurd’s poetry collection has consumed me the past few days. I understand now that my joy, as an American, is sitting on the backs of the lives that the West has taken.

This collection has given me something tangible to hold while I witness the terrors on the Middle East, on Palestine, on the world. Further, I feel that reading El Kurd’s journey from his childhood in Palestine to his schooling in the West has helped me understand the way stories were written in a certain way.

I urge people to read this collection, especially now. If you’re feeling like your world will never be the same, you are right. The world never was and will never be the same. In the West we live in an illusion. The narrative is always written by the same man.

Language is indeed powerful. History is powerful. This is more than a collection. When Palestinians are free, we can read El Kurd as a genocide that happened. As he writes, “One day we will write about dispossession in the past tense.”

‘Rifqa’ Review: A Deep Understanding of Palestinian History in El Kurd’s Narrative

Through El Kurd’s poetry, which is written in a conversational, storytelling style, readers will understand his family’s history and the many shared instances that have happened among Palestinian families. El Kurd’s play on alliterations, imagery, and metaphors to create a dissection of how deeply the genocide has impacted those who have lived. It leaves readers with a yearning, as El Kurd yearns for his homeland, and a call to action to make art, as it is an obligation, even if the reason we’re writing isn’t what we’d ever wish for.

Buying and Rental Options

Get recommendations on hidden gems from emerging authors, as well as lesser-known titles from literary legends.