As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

Have you ever wondered how great authors come up with their work? They steal from their favorite artists.

Well, it’s more complicated than that. Fortunately Harold Bloom summed up that creative process and came up with a six-step method to show how poets, playwrights and other writers craft their work. To understand how their favorite book came to be, authors and readers alike should pay attention to what Harold Bloom has to say in “The Anxiety of Influence.”

Great authors (think of Yeats, Shakespeare or Melville), Bloom argues, can’t cope with being unoriginal. However, it’s impossible to come up with something new under the sun. So, what do they do? They anxiously reinterpret their precursor’s work (forcing themselves to believe something was wrong or incomplete) in an effort to create something that feels authentic. That small misinterpretation creates a huge ripple effect in the world of literary influence, according to Bloom.

‘The Anxiety of Influence’ Summary: A 6-Step Program for Poetic Freedom

Harold Bloom explains that every great poet experiences an inner struggle to write their verses. The entire process is an anxiety-ridden ritual where an artist tries to break free from the influences of literary theory. Of course, such a thing doesn’t happen overnight but is a six-step task that takes an author from a first misreading up to the final confrontation with their precursors.

The 6 Steps

Each step is named as follows: Clinamen, Tessera, Kenosis, Daemonization, Askesis and Apophrades.

1. Clinamen, or Poetic Misprison

A poet first feels enthralled by poetry written by others, though that devotion turns into anxiety-fueled hate because they feel unable to create something that doesn’t feel like a copy of that once-loved work. Here, the poet will force themselves to misread their precursors’ verses so they can write something that feels original.

2. Tessera, or Completion and Antithesis

After forced misunderstanding comes completion, where the poet will finish what they deem incomplete or wrong. A poet must undergo the Tessera part of the process lest they lose their identity and succumb to the shadow of their precursor.

3. Kenosis, or Repetition and Discontinuity

The poet isolates themselves from their precursors after completing their work. Here’s where the breaking point happens: the poet frees themselves from influence and emerges anew.

4. Daemonization, or the Counter-Sublime

Harold Bloom believed poetry is an attempt to immortalize oneself through artistic creation. Here, the poet will become possessed by his attempt at apotheosis, though not a literal but literary apotheosis.

To achieve literary godhood, the poet must remove their precursor from the pantheon, effectively humanizing (reversing his status from poetical deity back to human) and replacing them (the poet becomes the poetical deity, thus saving themselves from death by echoing in literary history more than anyone else).

In a way, the poet takes away any influence, power, or prowess from their precursor for themselves. Past this step, the poet effectively replaced their precursor in their mind.

5. Askesis, or Purgation and Solipsism

The poet will now swerve from themselves and any other leftover influence. That way, they will re-emerge again free from any shred of influence (including their own) — or so they believe.

6. Apophrades, or The Return of the Dead

In this final stage, the poet finds themselves in complete solitude, which is almost as burdensome as influence, forcing the author to revisit what once were their precursors. The poet will make a last stand against their influences, where they can either succeed in their apotheosis or succumb to the shadow of their precursor.

Once you understand each step and how they work together, you’ll pick up on what every poet (and writer and, perhaps, every artist) does to create new work. Harold Bloom later released a companion piece called “A Map of Misreading,” which is a great read, but you need this book alone to understand Bloomean influence.

Editorial note: If you enjoy Harold Bloom, read our review of “The Western Canon”.

How Does Bloomean Influence Work?

Every major poet struggles against two ubiquitous forces: influence and death.

Influence comes by way of precursors (i.e., poets who rose to fame before the artist we’re talking about). An artist first falls in love with poetry by reading other poets’ work, then wants to create something of their own. The problem is that everything was said already (for there are only so many original thoughts humans can have in history), making the new poet feel small in the shadow of great artists. At that point, the poet can succumb to their doubts or anxiously, nervously, erratically reinterpret past work to deem it wrong or incomplete. That way, the new poet can write new verses to fix or complete previously published poetry.

Why would someone toil against art once held so dearly? That’s where death comes into play.

Major poets struggle against death and seek to immortalize themselves through their art — something that proves impossible if someone else holds the highest rank already. In their struggle against death, new poets will humanize their precursors in an attempt to immortalize themselves.

However, Harold Bloom makes a distinction: poets attempting to attain literary godhood have to drag their precursors down to the mortal realm once more. So a better way to describe what they’re doing is daemonization: They become possessed by their desire to achieve greatness.

Freudian thought plays a big part in Bloomean anxiety, too. Harold Bloom says there’s a family romance between the poet, the precursor (a father figure) and the Muse (a mother figure), where the poet will strive to be the Muse’s sole lover, which is a struggle of its own.

Retroactive Reinterpretation

The wonderful thing about Bloom’s interpretation of influence is that it’s a two-way street. Major poets will shape both the past and future by changing the way readers interpret poems.

Does that dynamic seem confusing? Take William Shakespeare (the most important author, according to Harold Bloom) as an example. Bloom claims The Bard of Avon was first influenced by Christopher Marlowe, only to swerve away from Marlovian influence to reshape the way we may read “Tamburlaine,” “The Jew of Malta” or “Edward II.” In a way, Shakespeare ends up influencing Marlowe (or rather, how we read Marlowe’s work), even though Marlowe died before Shakespeare could write his most defining (and influential) pieces.

You could see bits and pieces of Marlovian villainy in “Titus Andronicus” and “Richard III.” However, that influence dissipates with Shylock, where Shakespeare holds his own by creating a much richer, much more controversial character than the Marlovian Barabas. In doing so, Shakespeare reshapes the way we read “The Jew of Malta” in the light of “The Merchant of Venice.” Virgil made us read Homer in a new light, as Dante did with Virgil.

Not All Poets

Anxiety is not the predominant feeling in literature. It’s something reserved for the greats. Bloom claims every author feels the influence of his precursor, but only the great artists are bothered by it. Minor poets simply succumb to influence without a fight, while great geniuses will craftily work their way to the top.

Poets, in due time, triumph over their anxiety or succumb to the shadow of their precursor.

At The Rauch Review, we care deeply about being transparent and earning your trust. These articles explain why and how we created our unique methodology for reviewing books and other storytelling mediums.

‘The Anxiety of Influence’ Audience and Genre: Advanced Analysis for Literature Buffs, Scholars and Other Critics

This book is far from beginner-friendly. Harold Bloom’s literary knowledge knew no bounds. He would talk about Chaucer, Milton, Marlowe, Shakespeare and Jonson, then discuss Dante, Goethe, Freud and many more figures from literary tradition without skipping a beat. He will reference one book after the other as he constructs his theory of anxiety of influence in less than 200 pages.

It’s beautiful, eloquent and borderline genius, yes. It will also get on your nerves if you’re not ready to read plenty of references that will go over your head (if you’re not passionate about literature, that is. Even so, Professor Bloom always managed to sneak one reference that will surprise you, no matter how much of a literati you are). It’s important to note that Bloom will explain every reference when it’s central to the book’s thesis (e.g. when he cites Freud and Nietzsche, for example).

You will enjoy Harold Bloom’s “Anxiety of Influence” if you’re looking for a breath of fresh air after spending time in or reading about academia. Harold’s rather humane (and, perhaps, all too human) approach to understanding literature is uniquely amazing: poets, Bloom explains, forever compete with each other, both living and dead. That’s why literary influence is so pervasive.

Three Cs: Compelling, Clear, Concise

Editorial Note: We believe these three factors are important for evaluating general writing quality across every aspect of the book. Before you get into further analysis, here’s a quick breakdown to clarify how we’re using these words:

- Compelling: Does the author consistently write in a way that would make most readers emotionally invested in the book’s content?

- Clear: Are most sentences and parts of the book easy enough to read and understand?

- Concise: Are there sections or many sentences that could be cut? Does the book have pacing problems?

Compelling: Especially for Critics and Poetry Lovers

“The Anxiety of Influence” launched Bloom’s career and, in due time, turned him into one of the most famous literary critics of our time. The book, however, is polarizing: some love it, others find it to be Freudian nonsense. Bloom has influenced (and, in a way, exerted anxiety of influence on) countless critics who came after him.

Do you love literature, poetry specifically? You will love this book even if you don’t fully agree with all Bloom had to say. It’s a unique way to understand how poems beget other poems and how poets struggle with other poets.

Clear: Too Many Literary References Can Bog Down the Narrative

Clarity could be one of the main criticisms here. Harold Bloom, at times, loses himself in his train of thought and runs you over with one literary reference after another.

Bloom will often spend half a chapter to set the stage: a 20-page chapter will have 10 pages worth of Bloom talking about literary works before explaining the core concept. Is that necessary? Maybe. Does it feel redundant now and then? It does. Readers will notice that from time to time, Bloom comes up with recurring references that may confuse — instead of clarify — a point.

The occasional heavy rain of references mudding up clarity is but a speck on the radar. Bloom will clarify everything necessary when it matters most. For example, he takes the time to help the reader understand how subconscious relationships between poets exist whenever he heavily borrows from Freud’s work.

Concise: A Dense But Short Read

This work is as concise as it could’ve been — even if I mentioned Bloom takes quite a few pages to set the stage. “The Anxiety of Influence” is short: it’s less than 200 pages long and will take a few hours to finish.

I found two versions of this book online: The original version and a second edition that features a 50-page preface. The preface adds little value if you only care about what Bloom has to say about influence.

However, it’d be a great idea to read the preface after you’ve finished with the original portion of this book. The preface is a love letter to Shakespeare and a succinct explanation of how Marlowe influenced Shakespeare at first — and how Shakespeare shook off Marlovian influence in the second half of his career.

Prose Style: A Professor and Master of English, But With a Yiddish Twist

Bloom’s way of expressing himself was rather unique when writing and speaking. He was raised in a Yiddish-speaking household and learned English as a third language, so the way he wrote sometimes took a few unusual twists and turns, but nothing the average reader can’t handle.

Unusual prose is far from the highlight: imagery is recurrent in this book. In fact, Harold Bloom starts the first chapter by relying heavily on religious imagery. Make no mistake: the author is not invoking deities throughout but using “Paradise Lost” as an allegory where Satan is the poet and God his precursor. Similar literary imagery spawns throughout the book almost naturally.

It’s worth repeating that Harold Bloom lived for literature. He claimed to read a thousand pages per hour when young, according to New Yorker contributor Larissa MacFarquhar. You can tell the author of this book knows his way around literature backward and onwards from the many references he makes. Do you need to know Yeats by heart to understand the concept of anxiety of influence? Not quite, but it helps.

Something else worth mentioning is that, even though this book is about literary criticism, it’s far from a dry academic paper. Harold Bloom makes an effort (perhaps born out of having taught many years at Yale by the time he wrote this book) to make his point clear to the reader.

Rhetoric: Love for Literature, With Bits of Warning About Its Impact and the Mixing of Politics

There are three clear themes in this book. The core concept is about literary anxiety, but Bloom also touches on why someone should read and what literature isn’t.

Literary anxiety, you already know. Bloom backs every statement by drawing from Freud, Nietzche, and English-speaking poets. He will tell you how anxiety works, how it changes the way a poet writes and will use examples to explain it all.

Something interesting happens somewhere in the book. Bloom explains how poets treat each other (Artists work by stealing concepts and forcibly misunderstanding poems out of egotistical reasons) and uses that twisted relationship to point out that literature is far from useful for building character.

That way, Harold Bloom started what turned out to be his life-long campaign of keeping politics out of literature. What Bloom called resenters wanted to use books to play politics and enact ethical standpoints; Bloom himself said one should pursue literature out of pleasure alone.

If you agree with his theory of literary anxiety, it all makes sense.

Editorial Note: Read our review of Harold Bloom’s final book “Possessed by Memory”

Cultural and Political Significance: More Relevant Than Ever

One must be blind not to notice the ever-growing political pantomime taking place throughout Western countries in the last few decades. The so-called cultural wars are a tiresome game where vocal minorities win and the rest of us tirelessly lose ground. Harold Bloom called it before Twitter was a thing, and he got into a lot of trouble because of that.

Nowadays, anything cultural is both a target and a weapon. Art is inherently political. However, Bloom invites us to take a step back and look at art through different eyes. That’s not to say it’s a better way to interpret art — but it’s a way not influenced by politics, one that understands art for art’s sake, even if that means viewing great artists as desperate to climb to the top out of their fear of death.

Authenticity: A Genuine Love for Literature

It didn’t get more authentic than Harold Bloom when it came to his crusade in favor of literature. Bloom hasn’t fully developed his talking points against The School of Resentment in this book (he becomes more vocal against them later in his career), though he already explains who is causing trouble and why.

For Bloom, it all boils down to literature for literature’s sake. The anxiety of influence theory is a foundational piece to achieving that goal. Marxism, feminism, and other –isms have no place here. He taught literature at Yale for more than 60 years and amassed a fair number of detractors for going against the academic current. In the process, many people came to view him as the champion of the canon.

Teaching a subject at any institution doesn’t grant you a free pass to talk however you want. Harold Bloom having taught at Yale isn’t the reason why he has the literary pedigree to make his point across. The man, a self-professed desperate reader, spent his life reading and studying literature. This book is one of the fruits from that tree of knowledge called Harold Bloom.

So, was Bloom authentic when he wrote “The Anxiety of Influence”? Yes, he was. The man embodied a passion for literature like few could’ve had and used that knowledge to craft a unique way to interpret poetry.

Critiquing the Critics: Literature-Loving Consumers vs. The Literary Establishment and College Students Who Were Forced to Read the Book

Polarizing is the best way to describe Harold Bloom and his work. You either love or hate the man. Many love how passionate he was about literature. Others hated the condescending tone he used to criticize authors he deemed of a lower category. “The Anxiety of Influence” is no different.

Sites where laymen leave their reviews (like Amazon and Goodreads) are full of people who praise this book as eye-opening, while others criticize how Harold single-handedly talks down on their favorite authors.

Most one-star reviews, for example, come from people who had to read this for college. Three– and four-star reviews come from people who’ve read the book out of interest and may agree with parts or most of it. Five-star reviews come from people who love Harold Bloom and what he meant for literature.

Academics and critics have also found themselves on opposite sides. Few agree with Bloom fully, some agree on certain parts, and most academics (especially long after Bloom published this book) disagree with what he has to say, which shouldn’t be a surprise, considering Bloom went against well-established academic circles before and after his time.

John Hollander, for example, wrote a review for The New York Times around the release of “The Anxiety of Influence” that anticipated its effect on the literary community by stating that it “may outrage and perplex many literary scholars, poets and psychologists; in any event, its first effect will be to astound, and only later may it become quite influential, though in a different mode from the one it studies.” Dan Geddes gave similar praise by saying this book “made Bloom’s reputation, and remains respected work even by Bloom’s many detractors.” In 2023, Benjamin Madden argued against both statements by calling this book “Bloom’s one thought” that’s “a deceptively simple idea,” which “renders a common-sense maxim rich and strange by pushing it into a zone of extremity.”

‘The Anxiety of Influence’ Reviewer’s Personal Opinion: 3 Great Moments

I deeply admire Harold Bloom but am far from entranced by his persona. His views on literature are fascinating, and I doubt we’ll witness another towering figure like him soon enough. But I understand why he accumulated countless detractors throughout his career.

Why am I telling you these things? Reading “The Anxiety of Influence” is not my first rodeo with Bloomean ideas, which probably softened the hard landing some feel when they first get acquainted with the real-life version of Sir John Falstaff, Mr. Harold Bloom himself.

This book is not the perfect primer for someone unaware of how Bloom thought and expressed himself. He’s not yet the Harold Bloom who would carelessly charge against any book he disliked (from Harry Potter to “Infinite Jest” and other examples), but he does separate the wheat from the chaff by claiming Marxism, Feminism, New Historicism, and similar academic currents have no place in literature. Harold Bloom dealt with his anxiety of influence that way, by breaking free from his precursors and creating something different.

We’re not here to discuss Bloom but his book. It’s not his first, but it’s the one that launched him to fame and for good reason: Harold here analyzes not poems alone but the minds of the poets who wrote them and comes up with a great way to synthesize the process all great geniuses go through when facing their mortality. Yes, for Bloom, all great literature is a struggle to immortalize oneself, even if that means misinterpreting your precursors and removing them from the pantheon so you can make an apotheosis for yourself.

Three great moments take place in this book:

- The first chapter, where Bloom wonderfully paints a literary picture borrowing Milton’s Satan to explain how great poets feel

- The interlude, where Bloom helps us understand how we can use our newfound knowledge of literary anxiety to better interpret literature

- The last chapter, where Bloom expounds on the tragically last step every poet must face, a time when a poet must face his precursor on a final battle to determine whether the struggle was worth it or didn’t work — will they finally succeed in their apotheosis or succumb to the shadow of the great genius who lived before them?

I loved this book, but I see why this may not be for everyone. You have to love literature to dig deep and look for profound meaning in every major piece you stumble upon. Me? I’m starting to see the anxiety of influence in most major works I go back to, even outside of literature.

Editorial note: Read our article about Harold Bloom’s “School of Resentment”

‘The Anxiety of Influence’ Review: Spot On Way to View How Poets Relate to Each Other

The book works. It explains how poets feel overwhelmed by the greats who lived before them. Of course, that opinion may sound like wild speculation if Bloom simply stated his conclusion and drew from Freud to make his case. But far from it: Harold Bloom will first explain what literary anxiety is, then put poems to paper to showcase this mechanism in action.

Does Harold Bloom speculate a bit in “The Anxiety of Influence”? Absolutely! At times, he ponders how great poets could’ve been had they stayed away from anxiously misinterpreting their precursors.

However, he will leave no stone unturned. For Bloom, anxiety is a life-long ailment that is never fully out of the way. Major poets will have their creative zenith, then come down from that artistic peak to face their precursors once more. Once again, Bloom, in the last part of this book, will use several poems to showcase how this takes place. So, while he may speculate, he also has more than enough solid evidence to make his case.

This book helps us understand how poets relate to each other and how one poem may alter another in ways we could’ve never imagined. The interlude, as I already pointed out, helps the reader understand how to think like an anxious poet, allowing us to interpret the three versions hidden in every great poem: the poem a precursor wrote, the way the new poet will misinterpret it and how readers will reinterpret the first poem after that new poet writes new verses.

The new great poet will become someone’s precursor in due time, thus starting a new cycle of misprison that will continue as long as humans have a passion for poetry in their hearts.

‘The Anxiety of Influence’ FAQs

What is ‘The Anxiety of Influence’ by Harold Bloom about?

“The Anxiety of Influence” examines how poets struggle to create original work while influenced by past poets, feeling both admiration and rivalry.

What does “the anxiety of influence” mean?

It’s the creative tension artists feel when trying to forge their own path under the influence of past masters.

Who was Harold Bloom influenced by?

Harold Bloom was influenced by Romantic poets like Blake and Shelley, and he drew on Freud’s theories to shape his ideas on influence.

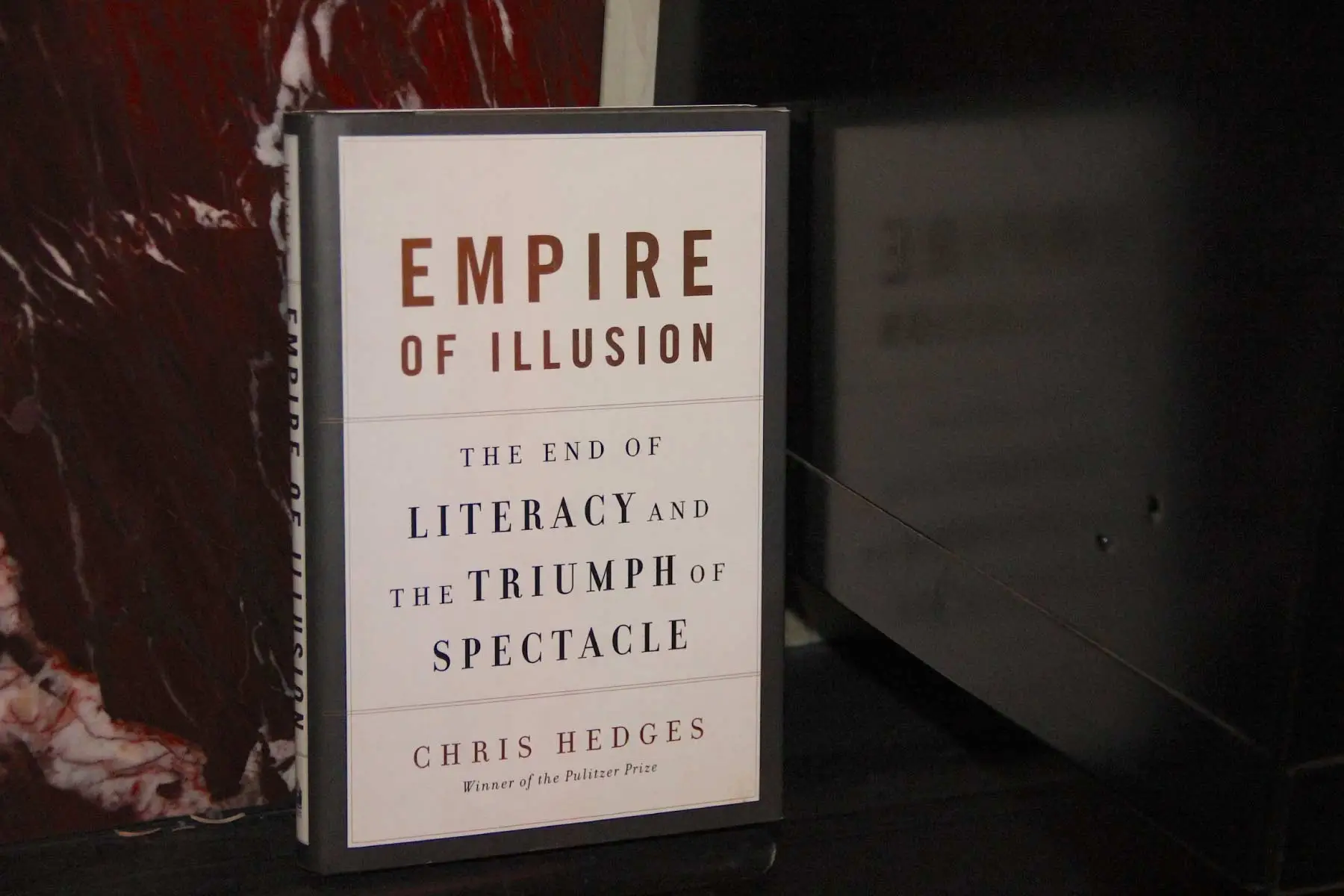

‘The Anxiety of Influence’ Buying Options

Text

Audio

Rental

Get recommendations on hidden gems from emerging authors, as well as lesser-known titles from literary legends.