As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

TLDR

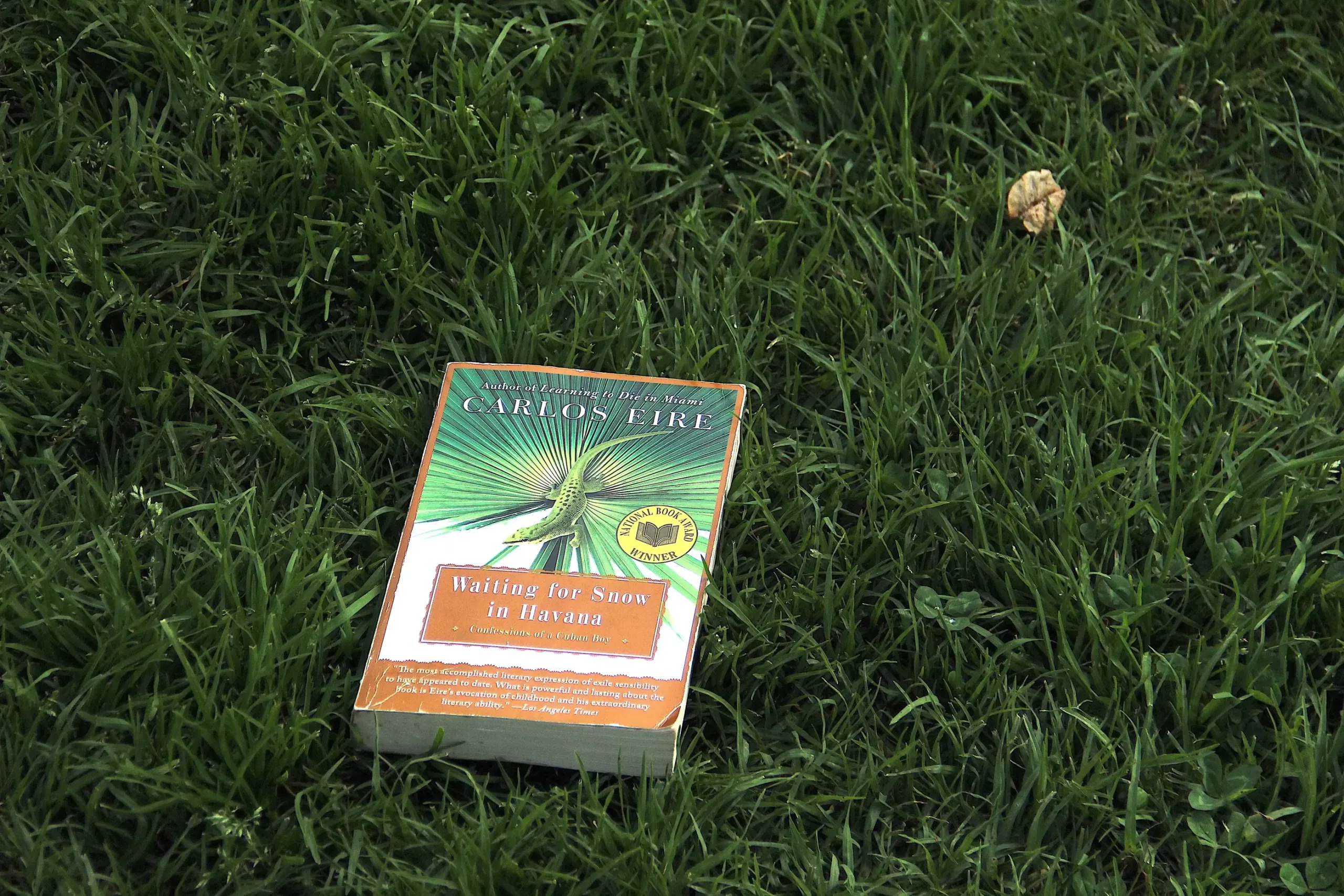

“Waiting for Snow in Havana: Confessions of a Cuban Boy,” a memoir by Carlos Eire, was a 2003 National Book Award winner. Boyhood reflections of life in Havana, Cuba are interspersed with stories of the author’s life after emigrating to the United States.

The author paints himself as a cruel, ugly person from the get-go. Young Eire spends his idle hours inflicting cruel pranks on animals, as well as people with physical and intellectual disabilities.

He fights a losing battle trying to gain reader empathy as the story develops. Readers eventually learn the author was sexually abused by his adoptive brother. Eire and his brother, Tony, endure endless hardships after Cuba’s sudden regime change and their subsequent relocation to the United States.

The descriptions of Fidel Castro’s brutal takeover of the Cuban government and the plight of Cuban children who suddenly became orphans in the United States is gripping and heart wrenching. However, the barrage of mean-spirited childhood pranks, overly dramatic and gory descriptions, harsh (and seemingly unreliable) judgements of others, and melodramatic religious fears and rants make the book a tedious read.

Love memoirs? You may also like our review of “Dear Senthuran”.

‘Waiting for Snow in Havana’ Summary: Cruelty, Political Instability and Immigration

“Waiting for Snow in Havana” is a memoir in which the author describes his mischievous and privileged boyhood in Cuba, executions of lizards, tormenting of mentally and physically disabled people, and how political instability led his parents to send him and his brother to the United States. Eire and his brother suffer great hardship, often living as orphans during their early years in the U.S. until their mother can finally unite with them.

After Batista is overthrown by Fidel Castro, Cuba descends into chaos. People lose their homes, businesses, and bank accounts. People disappear or are executed by firing squads, schools close, and bombs explode in neighborhoods.

In 1962, at age 11, Eire and his brother, Tony, travel to the U.S. as part of Operation Pedro Pan with 14,000 other unaccompanied minors. Eire lives with host families and in a Florida orphanage until his mother finally gains passage to the U.S. more than three years later. Eire’s father — now deceased — never leaves Cuba. Maria and her two sons struggle to survive as immigrants, working menial jobs and living in basement apartments. Eire eventually becomes a professor of history and religious studies at Yale University.

Promotional copy for “Waiting for Snow in Havana” fails to mention that the book is written by a man who was a very cruel and self-centered child.

Books Like ‘Waiting for Snow in Havana’

“The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba” by Chanel Cleeton similarly illuminates Cuba’s turbulent history although in an earlier era. Cleeton’s novel examines Cuba’s fight against Spanish rule in 1896, the plights of female revolutionaries and the role the U.S. played in this conflict.

Beyond the illumination of Cuba’s turbulent history, the similarities between these two books end. Cleeton’s book is a riveting historical novel that is easy to follow. Eire tortures readers with gory descriptions of endless cruel pranks and takes them on a turbulent journey with sudden shifts in time and place.

At The Rauch Review, we care deeply about being transparent and earning your trust. These articles explain why and how we created our unique methodology for reviewing books and other storytelling mediums.

Audience and Genre: Immigrant Biography May Appeal to Less Sensitive Readers

“Waiting for Snow in Havana” is listed under the genres of memoir, immigrant biographies and Cuban history. Historians or immigrants are most likely to enjoy this book. Many female readers and sensitive individuals will find it offensive. Male readers may be less troubled by Eire’s gory descriptions, mean-spirited pranks, propensity to torment and kill animals and steal things. Christians may find Eire’s unusual fears of Jesus and sacrilegious statements offensive.

“Waiting for Snow in Havana” steps outside the box of a typical memoir. It reads like a rant and long list of mean-spirited pranks. Occasionally the author surprises readers with action scenes, deep reflection or vivid descriptions, but those often get lost in the mire.

Readers lacking tolerance for cruelty to minorities, people with disabilities and animals will struggle to wade through this narrative, or they’ll possibly give up on the book. The author portrays his cruelty as if it is hilarious, when it strikes me as pathetic and revealing about his true nature. More sensitive readers might find solace in the ironic justice that is served when a tormented monkey bites him in the butt and the author later ends up working a menial job to survive while facing persistent racial discrimination.

Readers who have experienced a similar displacement from their native countries and can connect with the author’s plight might be more patient with his obsession with cruel, gory tales.

Three Cs: Compelling, Clear, Concise

Editorial Note: We believe these three factors are important for evaluating general writing quality across every aspect of the book. Before you get into further analysis, here’s a quick breakdown to clarify how we’re using these words:

- Compelling: Does the author consistently write in a way that would make most readers emotionally invested in the book’s content?

- Clear: Are most sentences and parts of the book easy enough to read and understand?

- Concise: Are there sections or many sentences that could be cut? Does the book have pacing problems?

Compelling: Turbulent Cuban History Grabs Reader Attention — The Rest is Mixed

What I found most compelling about “Waiting for Snow in Havana” was the plight of Cuba and this country’s people.

Early in the book, Eire describes a boyhood experience where his family ends up in the middle of a shootout during a car outing. A man fleeing from government officials begs them to help him. His father refuses. The man’s brutally executed body appears on the front page of the newspaper the next day. This pulse-pounding action scene and the gory aftermath introduces readers to the volatile nature of Cuban life that existed even under Batista’s rule.

Vivid descriptions illuminate the beauty and the dark sides of Cuba and urge readers to turn pages to learn more about the country. “Waiting for Snow in Havana” shines when Eire describes Cuba’s unique climate and beauty, the horrible suffering people endured after Fidel’s takeover, his memories of the country he loses, and the kind nature of people who help him settle in the United States.

Here are some examples of his descriptions of his native country. “The sunsets: forget it, no competition. Nothing could compare to the sight of that glowing red disk being swallowed by the turquoise sea and the tangerine light bathing everything, making all creation glow as if from within.”

Here’s Eire’s description of the Havana slums. “Whorehouses. Bastards. Corpses. Bribes, Beggars. Bright green phlegm on the sidewalk. At night, bats, mosquitoes, prostitutes, and flying cockroaches.”

Eire’s point-of-view quickly became exhausting. The author could win a prize for most unlikable narrator in a memoir.

“Waiting for Snow in Havana” is a labyrinth of a read. The reader faces routine jarring leaps in time and place. The author rants about religion and his hatred of Immanuel Kant and paints himself as a cruel and twisted individual. The book felt like a regurgitation of toxic thoughts and experiences and was very hard to follow.

Apparently, the cruel treatment he and other students suffered at his Catholic school led Eire to fear Jesus and God. Here’s an example of a statement he made. “The thought of Jesus coming to life on his cross and speaking to me seemed worse than Frankenstein, Wolf Man, Dracula, the Mummy, and the Creature from the Black Lagoon put together.”

Most readers will become engrossed in scenes about the turbulent political climate in Cuba and the author’s immigration to America. The endless descriptions of the author’s mean-spiritedness detract from the story. Eliminating many of these tales would improve reader empathy for the author and could shorten the book by one half.

It’s difficult to connect to anyone in this book. Readers may be repelled by the author.

Nonetheless, Eire’s mother, Maria, most often referred to as Marie Antoinette in the story, struck me as the most likeable character in the book. Due to her physical disability, she seemed unable to stop most of her son’s delinquent activities. She did make him return a stolen toy to a vendor at one point. The humiliation he suffered in this instance stopped him from stealing (after he had been engaging in this crime for years without guilt). Maria gave up her marriage, her family and her country to travel to the U.S. to live with her boys. She made the ultimate sacrifice for the sake of her sons.

“Waiting for Snow in Havana” readers may reflect on their religious beliefs when reading Eire’s rants about Jesus and his fear of eternally burning in hell. Eire has recurring nightmares about “bloody Jesus” watching him through their kitchen window. Whenever he had this dream, “It shook me to the core of my soul,” he says. Religion to Eire is all about fear of God and fear of hell and confessing your sins simply for the sake of being granted forgiveness. He never seems inspired to become a good person or experience true redemption of character.

He rants about temptation and how life is a booby trap in a “poor me” voice. Each temptation is there to make us suffer for eternity. His portrayal of God and religion horrified me as a Christian.

The irony is that Eire is afraid to swear at school in case he is struck dead on the spot yet seems disinclined to even try to be a decent person. His childhood self seems oblivious to the phrase that “actions speak louder than words.”

Due to the sacrilegious nature of many of the author’s comments — speaking Jesus’ name in vain, comparing Fidel’s appearance to that of Jesus, saying that his abusive, adopted brother had blue eyes like the painting of Jesus in their home, etc., — he may have renounced religion.

Readers are likely to react to Eire’s hateful rants about philosopher Kant, which randomly appears again and again in the text.

Readers are likely to experience horror over the cruelty of teachers at his Catholic school. I couldn’t help wondering if this inhumane treatment incited his own evil streak and fear of religion.

Brother Alexander warned them about shameful erections and how chauffeurs read dirty magazines. I’ll admit I laughed when the author shared how afraid he was that he might see a chauffeur looking at a naked woman in a magazine and end up in hell.

Eire’s third-grade teacher told the class terrifying stories about children who sinned and were taken straight to hell by a strike of lightning or the devil disguised as a black dog. His second-grade teacher hung dead stuffed animals along the walls. “Cross him one time too many and the next item on the wall might be your carcass,” Eire says in his signature melodramatic style. This teacher would punish a student by making him or her stand under the stuffed boa constrictor all day without a bathroom break, which inevitably led to pant wetting and humiliation. Reading these stories is enough to give one nightmares!

Clear: The Author’s Point is Often Clear as Mud

The sudden chronology shifts, litany of gory, cruel pranks that didn’t move the story forward, and long, nonsensical stream of consciousness rants, make the story hard to read.

The author’s point in writing certain chapters and sections is often unclear. Most of the time, it seems like his motivation is to upset or gross out the reader with his nasty descriptions and cruel behavior. Exploded lizards, bleeding hands, snotty noses and green phlegm, people burning in the flames of hell for eternity — it never ends.

The author is skilled at writing and inciting a reaction from the reader. His editor should have urged him to narrow down the book’s focus. Because it’s impossible to tell what it is. Cuba’s regime change? Hatred and fear of religion? The difficult life as an immigrant? I’m vying to win the prize for nastiest kid on Earth?

The overall story was complex. The author reflects on what he considers an idyllic childhood lost and how he ended up an orphan in the United States shortly after Fidel Castro’s Communist regime took over Cuba. There is a strong theme of abandonment in the story. He talks about Jesus being abandoned by God. Eire feels abandoned by his father, first, when he adopts Ernesto, and later, when he remains in Cuba instead of joining him and his blood brother in the States. Loss is also explored. The loss of his boyhood, his idyllic life, his native country.

There is another theme of reconciliation, where he uses the lizards he kills in large numbers as a symbol. This part was lost on me.

I often diverted to Google while reading this book. I didn’t remember who Immanuel Kant was. The narrative also mentions philosopher Johannes Eckhart, Plato and some unfamiliar statues. I never understood the point of the author bringing them into the story. It sometimes felt like he wanted to brag about how well-educated he was. To me, it simply solidified how judgmental and short-sighted he is.

Concise: Too Many Cruel Childhood Stories

“Waiting for Snow in Havana” would have been much more readable if Eir removed most of the nasty pranks from the narrative. Do readers really want to hear that he and his friends tried to shoot down airplanes? I would have liked to read more about how he adapted to life in the States. Readers are occasionally thrown into the author’s America experiences here and there but don’t get to stay there long enough to understand what his life is/was like or to learn whether he’s experienced any significant growth in character.

The pacing in the whole book didn’t work for me. There are too many rants and childhood pranks distracting from the main themes of the book, which make the book close to unreadable.

Character Development: Odious Narrator, Description of Others Suspect

Eire does a reasonable job of developing characters in the book, although I didn’t trust his portrayal of them. They seem one-dimensional, as if they only exist in the context of the author’s needs and wants.

His parents are mentioned most often in the book.

Eire’s father, Antonio, a local judge, believes he is a reincarnated King Louis XVI and that his wife, Maria, is the reincarnated Marie Antoinette. He also believes Eire’s brother, Tony, and adopted brother, Ernesto, were Bourbon princes in an earlier life. Antonio collects works of art, including a Saint Lazarus statue and a painting of Jesus that terrify the author. The implication is that the father cares more for these icons than his son. Eire portrays his father primarily in a negative light because of his choice to adopt Ernesto, who sexually tormented the author and his brother, and his choice to remain in Cuba instead of accompanying his mother to meet them in the States. Eire even changes his name to match his mother’s surname while in the U.S.

Eire’s mother had polio as a child and is crippled. She seems to have a strong sense of fairness. Although she often seems to be absent when he is causing trouble, she twice made him return toys when she recognizes them as stolen, accompanying him the second time to make sure he followed through. She endured a lot to get her two boys visas and get her own visa and sacrificed everything to live a disempowered life away from most of her family in a strange country.

Many other family members and friends are mentioned throughout the book. The author often shared how they suffered immeasurably under Fidel Castro’s government.

The book centers around flashbacks to childhood intermixed with leaps to more recent times. He also often uses Spanish phrases, word or phrase repetition, and poetic writing as devices in the book.

Story: Prepare for Sudden Time Leaps

Most readers will want to read about what happened in Cuba after Fidel Castro’s Communist government took over the country. They are also likely to be intrigued by scenes that describe the author’s experiences emigrating to the U.S. But he’s so unlikeable and some of his stories are so offensive. Readers may lose interest, be compelled to skip over some sections or find the book a chore to read. The sudden chronology shifts are also jarring.

“Waiting for Snow in Havana” ends with Eire and his brother at the airport, saying final goodbyes to family, flying over the sea, and having one last look at the lush countryside and the turquoise sea from the air. In Eire’s reflections and vivid descriptions, it is clear he is losing a lot making that trip. The ending felt satisfying.

Prose Style: Poetic and Engaging Writing Style

Eire has a unique and engaging writing style that is poetic in places. He isn’t afraid to step outside the box, even using sounds or word repetition or Spanish phrases to hammer home a point.

Eire does an excellent job of bringing readers on the scene. He even writes out sounds often to give a scene more impact. Narrative is overdone sometimes when the author regurgitates a long, boring rant about something.

Eire has a unique style of writing, as exemplified by the excerpts below:

The author describes seeing clouds shaped like Cuba on thousands of occasions and in many countries and states after leaving his native country for the last time. Cuba is never far from his mind. “‘There it is again,’ I’ll say when it appears out of nowhere, the crocodile-shaped island, my once and future lizard. So sublime, so ethereal, so far from reach, so clever and unfathomable, so supercharged with the power to enchant and annihilate me at the same time.”

Eire frequently shares his disillusion with God and Jesus as he does in the following sentences. “First these awful gifts, in a stinking stable, and then the cross at the end, in the prime of life. What kind of Father was God, to do this to his Son?”

In the same chapter, he says, “When I die I would like to be buried at a Christmas tree farm.” The author shows his preference for the commercial side of Christmas over the Christian one.

During this same holiday season, he describes Fidel Castro quite skillfully using Biblical terms. “Beelzebub, Herod, and the Seven-Headed Beast of the Apocalypse rolled into one, a big fat smoldering cigar wedged between his seething lips.”

The author uses metaphor, vivid imagery, paradox and a non-chronological writing style as literary devices. He sometimes speaks in a confessional voice.

Setting: Vivid Images of a Country Lost

“Waiting for Snow in Havana” is set in Havana, Cuba and various U.S. cities, including Miami, Chicago, rural Illinois and Minnesota. Eire grew up in Havana during the Batiste regime and continued living there for a year or so after Fidel Castro toppled the old government. Eventually he and his brother travel to the United States as part of the Pedro Pan program.

Eire writes poignant descriptions, bringing the reader right into his experiences. He paints vivid images of a beautiful turquoise sea, the brilliance of the sun, and Cuba’s tropical climate. He also creates images of what strikes him as ominous, such as the numerous iguanas and waters teaming with sharks.

The day before Eire leaves Cuba, he describes his last trip to the sea and how much it meant to him.

“It was a miracle. It had to be. You can’t doubt what you see. If this wasn’t a miracle, then nothing else could be.”

The color of the sea was changing, as if some giant brush were being applied from beneath. Or was it from above? I stared long and hard at the wild cloud-shaped rainbow in the water. There were splashes of tangerine in there, too, little bits of sunset at midday, along with splashes of blood red hibiscus blossoms.”

After describing a litany of negative religious images, he goes on to say…”But this fast-moving storm of shapes and colors within the turquoise water was a good miracle. It moved without stopping. Sometimes it split into two and the halves circled around to form a whole again. And in the meantime, as the halves danced with each other, the contrast between the cloud and the turquoise sea grew even more intense.”

I don’t know how long I stood there, or what I said. I had the strangest sensation of not having my feet planted on the ground.”

‘Parrot fish. It’s a whole school of them,’ said a man behind me.”

We all stood there on that dock, watching the miracle unfold for a long, long time…Eventually, the miracle vanished just as it had arrived. The colors moved farther and farther away, towards the horizon, northwards, riding the Gulf Stream, towards the United States.”

Snippets of his miserable years in Chicago are rife with imagery about the bitter cold, the whooping cough that nearly killed him, and a sexual assault on the subway. The factories are “flame-throwing smokestacks” and “omens of woe.”

His descriptions of Chicago exemplify how alien he feels in his new life. They can’t get adequate medical care. They’re unaccustomed to the harsh cold. And instead of the beauty he’s used to seeing, he’s surrounded by ugliness and an environment he finds alien and hostile.

Rhetoric: Convinces Readers He’s Mean and that Emigrating to the U.S. is Difficult

Eire addresses themes of sexual abuse, abandonment, political upheaval, immigration, loss and religion. Given his deplorable nature, he seems in a weak position to influence readers. Eire skillfully writes some scenes in a vivid and engaging way that brings readers come close to his experiences.

The author seemed like he was trying the hardest to sway readers to dislike certain individuals, such as his father, Immanuel Kant, Jesus and some of his Catholic school teachers.

The action scenes and stories about what became of relatives in friends convincingly portrayed Cuba’s downfall.

The stories about the mean teachers spoke for themselves, although I sometimes wondered if the author exaggerated these.

I found all the rhetoric in the book off-putting. Most of this took the form of long rants that came across as self-pity parties or personal attacks without much reason behind them.

Eire attempts to weave his own childhood experiences into the context of the political upheaval in Cuba and his relocation to the United States. The rants and the cruel childhood scenes didn’t blend in well with the story of a boy’s lost country and survival in a strange land.

Cultural and Political Significance: Cuban History and Parallels to Modern Authoritarianism

“Waiting for Snow in Havana” seems timely because it outlines how quickly bad leadership can send a country into turmoil, leading to undue hardship for citizens. Today in the United States, we are experiencing chaos under President Trump, who seems hell bent on inflicting cruelty on minorities, immigrants, the LGBTQ population and common people. Suddenly we are witnessing people deported without reason (even to concentration camps in El Salvador), groups of people being denied that they exist, government agencies gutted, and many people living in fear over the security of their jobs or social service programs.

“Waiting for Snow in Havana” includes snippets of Eire’s life from the 1950s up to contemporary times. It centers around the author’s boyhood years leading up to Fidel Castro’s takeover of the Cuban government in 1962 and then his life after he and his brother migrated to the U.S.

I have never visited Cuba and know only a little about its history, so I can’t vouch for the accuracy. Eire seems to have a flair for drama, so my inclination is to say some events may be overplayed.

This memoir will likely resonate with people who fled from their native country during a time of political upheaval.

Because Eire was on the ground in Cuba and several family members and friends were involved in the underground movement, “Waiting for Snow in Havana” includes unique insights. His cousins Miguelito and Fernando helped a rebel group blow up a ship full of weapons and explosives in Havana’s harbor. Miguel was later killed by a firing squad. Fernando embarked on a failed plot to kill Castro and eventually ended up in prison.

Eire’s stories about family members and friends losing their homes and businesses brings the reader on the scene to Cuba’s deterioration. His uncle Mario lost his two businesses and burned the accounting records so the state wouldn’t be able to collect from anyone who owed money.

He talks about the loss of things they enjoyed, as well as essentials such as medicine, clothing, cars and hardware. They were even forbidden from seeing “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” and other movies they’d seen many times before.

“No more comic books. No more American films. No more American television programs. No more ice-cream man. No more shaved-ice man. No more fruit man. No more vegetable man. No more coal man. No more guarapo man. No more Jamaican pastry man, and no pastry man song.”

Eire said Coca Cola even tasted bad because Castro snatched away the company but neglected to obtain the formula to make the soda.

“A lifetime of memories gone in less than a year. An entire culture pulled up by the roots.”

He describes spying on Che Guevara, “the man who wants to do away with money” who lives in a mansion and drives a Mercedes-Benz.

They hear the bombs explode at the event later called the Bay of Pigs when the CIA attempted to topple Fidel’s government. The Americans abandon the armed exiles from Florida they sent to Cuba to attack. Many of them are slaughtered. Eire’s uncle Fido is arrested that day.

Authenticity: Events Seem Believable, Portrayal of People Not So Much

The author struck me as an unreliable narrator due to his cruelty, lack of ethics and tendency to descend into melodrama. Much of the narrative seemed to be written to offend the reader and came across as exaggerated. His scenes about political events seemed more believable than his portrayal of the book’s characters or the interactions between them.

The author is a harsh critic of many people in the book, including his father, his adopted brother, and the philosopher, Kant. I didn’t trust Eire enough as a narrator to accept these portrayals. Someone who is cruel and mean and spoiled and has close to zero self-awareness isn’t the kind of person you can trust to accurately characterize others.

Critiquing the Critics: Undeserved Critical Acclaim and a Mixed Consumer Response

Publishers Weekly praised the book. I was unable to access the New York Times review. According to The Rauch Review’s editorial team, the New York Times praised the book for its urgency and emotional depth. It appeared that critics could read past the cruel pranks, stream-of-consciousness rants and sudden chronology shifts.

Amazon and Goodreads reviewers tended to either love or despise the book. Many reviewers connected with the author’s honest writing and the reflections on his childhood. Others found it annoying that Eire felt compelled to focus on his cruel pranks. Some referred to the author as a spoiled and hateful child. Another said it was “more a tribute to excess and cruelty than anything else.” Readers often praised Eire’s vivid descriptions. Some described his writing as poetic. Others griped about the sudden time and place shifts.

I agreed with many of the reviews, except those that described the book overall as brilliant. I found the book too flawed to receive such rave reviews.

Book Aesthetic: A Mismatch Cover Starring the Often-Murdered Lizard

The “Waiting for Snow in Havana” front cover displays a green lizard on a palm frond, which establishes Cuba’s tropical setting and a creature the author despises. A book description covers the back.

My copy of the book did not include promotional content, but newer editions on Amazon include a quote from the Los Angeles Times and a medallion mentioning that the book was the 2003 National Book Award winner.

The latest covers are artistic with a splash of commercial.

To me, the cover suggests a travel memoir or book set in a tropical locale. It doesn’t set the stage for all the chaos and mayhem in this book. I found it odd that a creature the author hates so much is placed at the center of the cover. This cover seems like one a nature-loving author would choose.

Reviewer’s Personal Opinion: Narrator Turned My Stomach

To me, the most intriguing aspects of “Waiting for Snow in Havana” were the vivid descriptions of Cuba, the tragic stories of the country’s downfall, and the raw portrayals of starting over in the United States. It is obviously traumatic to be wrenched away from your native country as a boy, to have no stable home, and experience constant discrimination.

The vivid descriptions of Cuba’s beauty made me want to visit, despite the country’s continued troubles. I find tropical places appealing and would appreciate Cuba’s beauty.

I empathized with Eire deciding to drop his father’s surname, Nieto, and use his mother’s surname, Eire, instead. Although it was unclear if he did it to honor his mother or to spite his father. His mom endured much hardship to get her boys out of the country, and his father didn’t help her with the paperwork.

I appreciated the rare instances where Eire feels remorse about a dastardly deed he once did. At one point when he is in the U.S., he reflects on what he once was.

“We were spoiled brats, niños bitongos, who thought we’d never have to worry about cleaning out pool filters. Served us right, it did, to be hurled down to the bottom of the heap when we reached the States. I once spent an entire summer, between high school and college, working sixty hours a week at my mother’s factory, inserting thousands of screws in the morning and taking out the same screws in the afternoon, day after day. They were temporary screws, put in place to speed up the bonding power of a special glue between two parts.”

Toward the end of the book, when Eire and his brother prepare for their trip to the States, he mentions his passport photo and how when he presented it, he recalled how when the picture was taken, he’d worn a formal suit jacket with pajama bottoms.

“When I finally get to show that passport at the airport, on the day I leave Cuba for good, I feel a strong urge to laugh. There I am, about to be strip searched, and I’m showing these very important guys a picture that is a joke of sorts. I am not what I seem to be.”

“I’m turning into a chameleon, or into one of Addison’s brown iguanas. I’m camouflaged. I blend in so well as a respectable Cuban boy from a good family, but underneath I am a rebel, a worm, and a refugee in the making. I’m wearing my God-damned pajamas.”

I found Eire’s cruelty to animals and disabled people triggering. I honestly found his personality intolerable.

Eire also comes across as weak — he’s constantly crying, whining, and afraid. He has so many nightmares during his childhood, he sleeps in his parents’ bed most of the time. He’s a spoiled child, eager to inflict cruelty on others yet constantly pities himself. He cries whenever he faces hardship until he’s forced to grow up while living in the States. Part of the reason Eire had such a hard time adapting to life in the US is that he was a spoiled child. He had never prepared a meal or done chores or housework.

He also has zero compassion for others. This description of a legless Black woman who begged outside their church exposes this sad truth. “She just sat there Sunday after Sunday, her stumps on display, her little drooling boy stretched across her lap, her hand outstretched for alms…He was so thin he looked more like a skeleton than a living, breathing boy.”

I had no tolerance for her pain, or her neediness, or her drooling boy.”

Annoyed by her presence, he asked his parents why she was always there. It isn’t clear whether they gave her any money. Eire probably wouldn’t have found any act of compassion notable anyway.

One time he goes to confession and mentions saying he is sorry when he actually isn’t. He’s basically telling the reader he learns nothing from his mistakes. I prefer a memoir written by a narrator who experiences personal growth during the story.

I found his harsh criticism of Immanuel Kant laughable. I wasn’t familiar with this philosopher’s teachings. From what I read, it appears that Kant believed that morality should be defined by recognizing our universal oneness and the value of every individual over needing someone to assert control to be “good” (such as state or federal laws or religious doctrines). I don’t see any reason for Kant to be ripped upside and down the other for having this belief. Some of us want to be kind and bring uplift to the world because we can! I grew up near a river and forest and not once, felt tempted to kill any wild animals. I felt a connection to them.

Kant also believes that thoughts create experience. I also share this belief. I didn’t feel like the author was in much of a position to judge others because he is the kind of person I would steer clear of at all costs. I don’t understand why Eire can’t respect that others may have views different from his owns without hating them. I found that so bizarre.

When the author mentions how his grandmother, Lola, shares his hatred of lizards, he goes on to pontificate about the Adam and Eve story and to say that God himself hates lizards, frogs and snakes. He never acknowledges that man is the most destructive and harmful creature on earth. It becomes exhausting reading a story told by such a twisted narrator.

I didn’t find the character portrayals reliable, given that Eire’s perceptions of the world seemed so twisted. The most likeable characters in the book seemed to me Eire’s mother, Maria, and his mother’s sister, Lily. Both lived selflessly and cared for others.

I am interested in Cuba’s history and wanted to read about it. I felt compelled to review “Waiting for Snow in Havana” because I reacted strongly to it for a variety of reasons.

Up next: Dive into our review of “The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge”.

‘Waiting for Snow in Havana’ Review: Endurance Contest to Read

This memoir overall didn’t work for me. My rating is 3 stars. The leaps back and forth in time (minus .5), the endless parade of cruel pranks (minus 1), the needless attacks on Immanuel Kant (minus .25) and the religious rants (minus .25) detracted from the effectiveness of Eire’s book.

I wanted “Waiting for Snow in Havana” to be about the plight of a boy trying to adapt to living in a new country with interspersed reminiscences about life in his home country and the suffering people endured during the regime change. An endless mire of rants and cruel acts bury these themes of interest.

Buying Options

E-Commerce Text and Audio Purchases

E-Commerce Audio Only

Physical Location Purchase and Rental Options

“Waiting for Snow in Havana” is available in most bookstores, including independent bookstores. It is listed under the genres of memoir, immigrant biographies and Cuban history.

Digital Rental Options

“Waiting for Snow in Havana” is available in most libraries and can be found on library apps such as Libby and Overdrive without a wait.

Get recommendations on hidden gems from emerging authors, as well as lesser-known titles from literary legends.