At The Rauch Review, one of our biggest themes is critiquing every type of gatekeeper in the literary world, as well as the overall process and mindset of literary gatekeeping. It’s especially relevant for us to criticize literary journal operators because The Rauch Review actually has the power to address their shortcomings. In addition to being a publication with a populist mindset on the world of books and its intersection with politics, we are a literary journal. Like many publications, we blend articles and book reviews with original creative writing pieces.

We are not 100% against gatekeeping in literary journals. After all, we have now become a literary gatekeeper. We will inevitably say no to some pitches and submissions. We’re a publication, not a free-for-all platform like Medium. To maintain our editorial direction and standards, we can’t say yes to everyone.

What we’re advocating for is literary journal gatekeeping that is more fair, consistent, economic, clear and inclusive. With this article at your disposal, please hold us accountable as well.

What Are the Shortcomings of the Average Literary Journal?

Literary journal gatekeeping is often excessive, inconsistent, extortive and classist. My colleagues and I learned this reality the hard way during our undergraduate degrees and the young years of our professional careers. A few of my colleagues with MFAs have also encountered excessive gatekeeping.

Academic Elitism and Rejecting Submissions That Meet Guidelines

At first it didn’t seem so hard to consistently get published in literary journals. During my undergraduate degree and creative writing minor at NYU, I published many of my short stories in several literary journals, both university-based and open to anyone.

After I graduated, however, my chance of acquiring a new literary journal byline immediately plummeted. Once I had been out of school for a few years, getting into literary journals seemed impossible. It didn’t matter how much effort I put into writing, how badly I wanted to improve, how much I trained with editors or how much I triple checked the submission guidelines. Even when my submission and identity perfectly fit the description of the journal’s preferences, they said no, and without feedback.

It was frustrating. Because I had become a professional writer with consistent access to experienced editors, everyone agreed my skill level was improving over the years. My stories were similar to what I had submitted as a student. Yet the rejection ratio remained. Unless I’m forgetting something, I think I haven’t been able to publish in a literary journal since 2014.

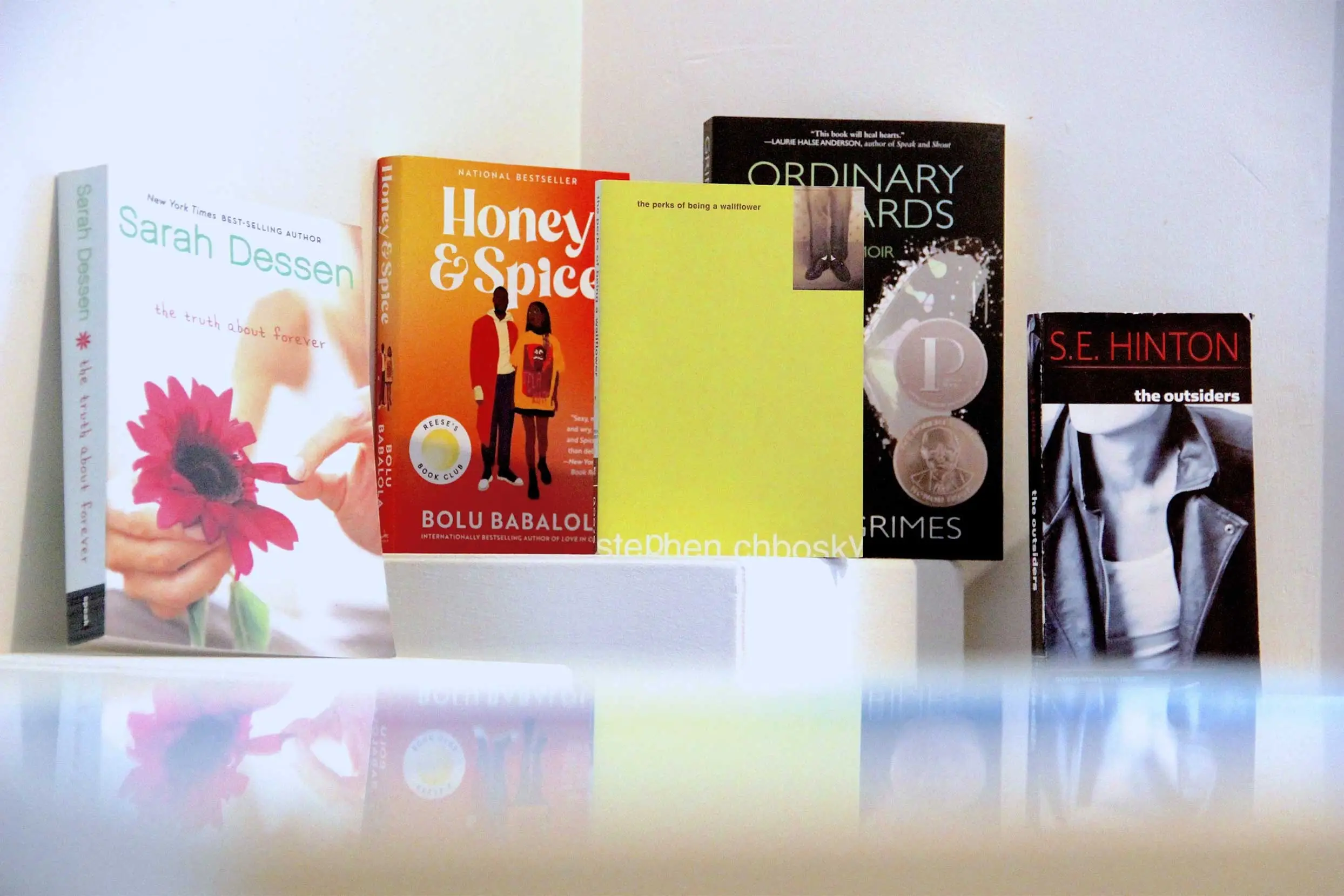

The more my network expanded, the more people I found who were in the same situation. When we discussed our grievances, we always arrived at the same conclusions. Literary journal operators were filtering based on subjective preferences that weren’t mentioned in their guidelines. People in academia had a huge advantage, especially graduate school and Ph.D. students.

Maybe it’s OK for students to have a slight edge. They and their families are paying exorbitant tuition, sometimes taking on a lifetime of student loan debt. Both undergraduate and graduate programs often don’t provide practical work skills. The primary value points are the college experience and network.

Nonetheless, there shouldn’t be a huge disparity between people in and outside the academic bubble. I imagine the gatekeeping is even worse for people who can’t afford a bachelor’s degree. They don’t even get inside the bubble in the first place, and I haven’t seen any outreach programs targeted toward them. People who run literary journals tend to preach about equality, yet their approach to submissions is elitist and classist.

Submission Fees

If literary journals hadn’t normalized the practice of making people pay just to submit their work for consideration, I don’t think anyone would entertain submission fees. I insist on calling them “submission fees” instead of “reading fees” because there is no guarantee editors read every submission in full. When all rejectees receive is a canned email, how can they know an editor looked at anything more than submission information and the title of the piece?

Submission fees are the practice of extracting as much money as possible from ambitious writers who want validation from outlets they perceive as prestigious. Literary journal operators are not obligated to provide applicants with anything in return. Many of the literary journals that charge for submissions claim to be nonprofits, yet charging $25+ per submission could be highly profitable if you have thousands of applicants every season and minimal overhead.

When They Like Your Piece and Think It’s Good, But Not Enough to Publish It

Based on my experience and discussions with colleagues, some literary journals send two types of rejection emails. These are usually canned. Some journal editors will write something manually, especially if they are using a shared email account (what we do) instead of a submission system.

- The no, with no feedback or mention of anything positive about your piece.

- The no that says they liked your piece and think it’s good (not useful feedback), but they have to say no because it “does not meet our needs” or something to that effect. They’re saying you were close — perhaps getting close to their unspoken subjective preference — but not close enough.

This second type of rejection reveals the journal’s goal of excessive exclusion. They think the submission has a high level of quality and meets their guidelines, yet they’re choosing not to publish it. They have space to publish it and believe it has quality deserving of publication, but they’re worried it would tarnish their brand.

The Typical Defenses Literary Journal Editors Use Against These Criticisms, and Why Most of Them Are Weak

When I was fresh out of college, I tried to give literary journal operators more slack. I hadn’t managed a publication. Perhaps there were fair reasons for their excessive gatekeeping.

In 2015, however, I became a managing editor and publication operator, in addition to being a writer. The Rauch Review is, in part, the result of my many years in this line of work.

I didn’t manage a literary journal back then, but the publication and process was similar. The outlet was a mental health blog attached to a startup that had become well known. Our site readership was more than 100,000 people a month, with tens of thousands on our email list. Because mental health was the main topic, we published many creative nonfiction pieces about relationships and mental illness.

At the height of our popularity during my tenure at the company, we received dozens of pitches every week that were similar to literary journal queries. The only rejections I sent were to people who clearly hadn’t read the blog or couldn’t write something that was readable and even somewhat compelling. Most of my responses explained why I was saying no. I’ll admit I struggled with feedback on the submissions with bad, unreadable writing. Is there a 100% sensitive way to explain to someone exactly why their writing is bad?

I said yes to everything I possibly could. Unlike many literary journals, we actually paid every published contributor, so there was a budget I had to stay within. Still, my acceptance versus rejection ratio must have been around 60:40. Compare that figure to the average literary journal that accepts only a fraction of submissions.

It’s not like generosity to writers was my only motivation. I wanted to publish more pieces because more content usually led to more traffic and ultimately more revenue.

With the context of my experience, let’s examine the typical literary journal operator defenses against the criticisms I laid out earlier.

The Defense: Not Enough Money

‘We would publish more people, but we don’t have the money.’

This defense is only valid under this very specific set of circumstances:

- The journal pays people for published contributions.

- The journal does not have a funding source that is large and consistent: an academic institution, a corporate backer, wealthy individuals who love literature, consistent grassroot donations, the operators have day jobs that pay well enough to have disposable income that could be put toward the journal, etc.

- The journal doesn’t charge submission fees.

- The journal doesn’t sell anything or accept donations. Or they do sell and accept donations, but the money is negligible because they don’t have the following or marketing skills to drive revenue.

- The journal is designed, developed, maintained and marketed well enough to have significant operating costs.

For me to accept the money defense, every single one of these points needs to be true simultaneously and consistently. For most journals, only one or two of these points apply at any given time.

My Take: Money Is Not a Big Factor in Literary Journals, and Publishing More Can Help With Money

If you don’t have a lot of money to pay published contributors, simply tell them so, and see who will do it for free. You don’t have to pay contributors. People who are interested in your journal — or so desperate to get a byline anywhere that they don’t care who you are and whether you pay — will still submit.

Most literary journal submitters are not in it for money. Even highly trafficked literary publications such as Narrative only pay out a small amount to the tiny fraction of people who place highly in their contests.

If your journal runs on donations, submission fees, product sales or a combination, publishing a higher number of unpaid contributors will help drive revenue. More people will share their work and encourage peers to submit. More content usually means more traffic, and more traffic usually means more money.

There is a cost if all of your published pieces have feature images, but this cost is very small in my experience. If you can’t afford a designer or photographer, you can do cheap stock photos. Reasonable people will understand. They’ll be happy to get published, regardless of the image that accompanies their piece.

The Defense: Not Enough Time

‘We’re busy. We’re not doing this for money. We’re doing it out of love for literature. We don’t have time to accept more people.’

My Take: Valid, But There is a Better Approach

As a managing editor, it’s true that accepting more people means spending more time. If you become overwhelmed, there’s an easy solution: close submissions until you’re not overwhelmed. This approach is better than keeping submissions open but not actually considering them thoroughly. Don’t waste time, whether it’s yours or others.’

The Defense: Limited Space

‘We can only fit so many people in our next season.’

My Take: The Internet Is Limitless

This excuse is valid for physical magazines. For digital publications, however, this excuse is even more lame than the time and money ones.

There’s no way literary journal operators are running out of space on their websites. I once managed a blog that published around 20 posts a week. We did not have any file or data storage problems.

The Defense: We Want Our Publication to be Exclusive

‘If we published more people, our journal wouldn’t be as exclusive.’

My Take: Finally, Honesty

This defense is the most valid by far because it’s honest. It’s actually really refreshing when literary journal operators admit their goal of excessive exclusion. I’m not mad about it. It’s only a difference of opinion and ideology. People can run their outlets how they want. I only wish they would express the sentiment more often in their guidelines.

All of the other defenses are distractions from this one. Journal operators are worried that, if they admitted the truth, there would be an unpleasant backlash.

The Rauch Review Approach to Literary Journal Pitches and Submissions

To address the shortcomings of the average literary journal, we have developed these practices and guidelines:

- We have clearly defined pitch/submission guidelines and standards of writing quality. We will publish anyone who follows our instructions and meets our standards. We do not care about academic background, awards, past writing experience or identity.

- If we are short on time and resources needed to fairly consider contributions and pay contributors, we will temporarily close pitches and submissions.

- If the volume of submissions we want to publish becomes too great for us to afford our $100 minimum, we will make an announcement and solicit free contributions.

- To prove we read your submission, our rejection responses contain specific feedback. We want this feedback to be useful.

- To prevent people from wasting time writing a full submission for us only to be rejected, we insist on doing the pitch step first.

- We do not charge submission fees. If we ever change this policy, we will send a detailed explanation.

Join us in making the literary world a less elitist space.